Copyright (c) Hyperion Entertainment and contributors.

SMUS IFF Simple Musical Score

“SMUS” IFF Simple Musical Score

- Document Date

- February 20, 1987 (SID_Clef and SID_Tempo added Oct, 1988)

- From

- Jerry Morrison, Electronic Arts

- Status Of Standard

- Adopted

Introduction

This is a reference manual for the data interchange format “SMUS”, which stands for Simple MUsical Score. “EA IFF 85” is Electronic Arts’ standard for interchange format files. A FORM or “data section”) such as FORM SMUS can be an IFF file or a part of one. [See “EA IFF 85” Electronic Arts Interchange File Format.]

SMUS is a practical data format for uses like moving limited scores between programs and storing theme songs for game programs. The format should be geared for easy read-in and playback. So FORM SMUS uses the compact time encoding of Common Music Notation (half notes, dotted quarter rests, etc.). The SMUS format should also be structurally simple. So it has no provisions for fancy notational information needed by graphical score editors or the more general timing (overlapping notes, etc.) and continuous data (pitch bends, etc.) needed by performance-oriented MIDI recorders and sequencers. Complex music programs may wish to save in a more complete format, but still import and export SMUS when requested.

A SMUS score can say which “instruments” are supposed play which notes. But the score is independent of whatever output device and driver software is used to perform the notes. The score can contain device- and driver-dependent instrument data, but this is just a cache. As long as a SMUS file stays in one environment, the embedded instrument data is very convenient. When you move a SMUS file between programs or hardware configurations, the contents of this cache usually become useless.

Like all IFF formats, SMUS is a filed or “archive” format. It is completely independent of score representations in working memory, editing operations, user interface, display graphics, computation hardware, and sound hardware. Like all IFF formats, SMUS is extensible.

SMUS is not an end-all musical score format. Other formats may be more appropriate for certain uses. (We’d like to design an general-use IFF score format “GSCR”. FORM GSCR would encode fancy notational data and performance data. There would be a SMUS to/from GSCR converter.)

Section 2 gives important background information. Section 3 details the SMUS components by defining the required property score header “SHDR”, the optional text properties name “NAME”, copyright “(c) ”, and author “AUTH”, optional text annotation “ANNO”, the optional instrument specifier “INS1”, and the track data chunk “TRAK”. Section 4 defines some chunks for particular programs to store private information. These are “standard” chunks; specialized chunks for future needs can be added later. Appendix A is a quick-reference summary. Appendix B is an example box diagram. Appendix C names the committee responsible for this standard.

Reference

“EA IFF 85” Standard for Interchange Format Files

describes the underlying conventions for all IFF files.

“8SVX” IFF 8-Bit Sampled Voice

documents a data format for sampled instruments.

MIDI: Musical Instrument Digital Interface Specification 1.0, International MIDI Association, 1983.

SSSP: See various articles on Structured Sound Synthesis Project in Foundations of Computer Music.

Electronic Arts is a trademark of Electronic Arts.

Amiga is a registered trademark of Amiga, Inc.

Background

Here’s some background information on score representation in general and design choices for SMUS.

First, we’ll borrow some terminology from the Structured Sound Synthesis Project. [See the SSSP reference.] A “musical note” is one kind of scheduled event. Its properties include an event duration, an event delay, and a timbre object. The event duration tells the scheduler how long the note should last. The event delay tells how long after starting this note to wait before starting the next event. The timbre object selects sound driver data for the note; an “instrument” or “timbre”. A “rest” is a sort of a null event. Its only property is an event delay.

Classical Event Durations

SMUS is geared for “classical” scores, not free-form performances. So its event durations are classical (whole note, dotted quarter rest, etc.). SMUS can tie notes together to build a “note event” with an unusual event duration. The set of useful classical durations is very small. So SMUS needs only a handful of bits to encode an event duration. This is very compact. It’s also very easy to display in Common Music Notation (CMN).

Tracks

The events in a SMUS score are grouped into parallel “tracks”. Each track is a linear stream of events.

Why use tracks? Tracks serve 4 functions:

- Tracks make it possible to encode event delays very compactly. A “classical” score has chorded notes and sequential notes; no overlapping notes. That is, each event begins either simultaneous with or immediately following the previous event in that track. So each event delay is either 0 or the same as the event’s duration. This binary distinction requires only one bit of storage.

- Tracks represent the “voice tracks” in Common Music Notation. CMN organizes a score in parallel staves, with one or two “voice tracks” per staff. So one or two SMUS tracks represents a CMN staff.

- Tracks are a good match to available sound hardware. We can use “instrument settings” in a track to store the timbre assignments for that track’s notes. The instrument setting may change over the track.

- Furthermore, tracks can help to allocate notes among available output channels or performance devices or tape recorder “tracks”. Tracks can also help to adapt polyphonic data to monophonic output channels.

- Tracks are a good match to simple sound software. Each track is a place to hold state settings like “dynamic mark pp”, “time signature 3/4”, “mute this track”, etc., just as it’s a context for instrument settings. This is a lot like a text stream with running “font” and “face” properties (attributes). Running state is usually more compact than, say, storing an instrument setting in every note event. It’s also a useful way to organize “attributes” of notes. With “running track state” we can define new note attributes in an upward- and backward-compatible way.

Running track state can be expanded (run decoded) while loading a track into memory or while playing the track. The runtime track state must be reinitialized every time the score is played.

Multi-track data could be stored either as separate event streams or interleaved into one stream. To interleave the streams, each event has to carry a “track number” attribute.

If we were designing an editable score format, we might interleave the streams so that nearby events are stored nearby. This helps when searching the data, especially if you can’t fit the entire score into memory at once. But it takes extra storage for the track numbers and may take extra work to manipulate the interleaved tracks.

The musical score format FORM SMUS is intended for simple loading and playback of small scores that fit entirely in main memory. So we chose to store its tracks separately.

There can be up to 255 tracks in a FORM SMUS. Each track is stored as a TRAK chunk. The count of tracks (the number of TRAK chunks) is recorded in the SHDR chunk at the beginning of the FORM SMUS. The TRAK chunks appear in numerical order 1, 2, 3, .... This is also priority order, most important track first. A player program that can handle up to N parallel tracks should read the first N tracks and ignore any others.

The different tracks in a score may have different lengths. This is true both of storage length and of playback duration.

Instrument Registers

In SSSP, each note event points to a “timbre object” which supplies the “instrument” (the sound driver data) for that note. FORM SMUS stores these pointers as a “current instrument setting” for each track. It’s just a run encoded version of the same information. SSSP uses a symbol table to hold all the pointers to “timbre object”. SMUS uses INS1 chunks for the same purpose. They name the score’s instruments.

The actual instrument data to use depends on the playback environment, but we want the score to be independent of environment. Different playback environments have different audio output hardware and different sound driver software. And there are channel allocation issues like how many output channels there are, which ones are polyphonic, and which I/O ports they’re connected to. If you use MIDI to control the instruments, you get into issues of what kind of device is listening to each MIDI channel and what each of its presets sounds like. If you use computer-based instruments, you need driver- specific data like waveform tables and oscillator parameters.

We just want some orchestration. If the score wants a “piano”, we let the playback program find a “piano”.

A reference from a SMUS score to actual instrument data is normally by name. The score simply names the instrument, for instance “tubular bells”. It’s up to the player program to find suitable instrument data for its output devices. (More on locating instruments below.)

A SMUS score can also ask for a specific MIDI channel number and preset number. MIDI programs may honor these specific requests. But these channel allocations can become obsolete or the score may be played without MIDI hardware. In such cases, the player program should fall back to instrument reference by name.

Each reference from a SMUS track to an instrument is via an “instrument register”. Each track selects an instrument register which in turn points to the specific instrument data.

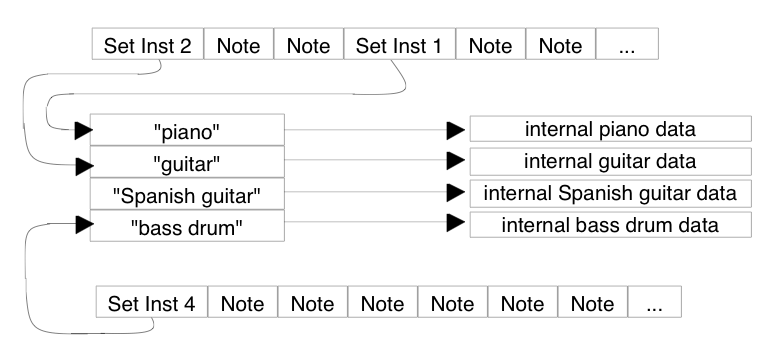

Each score has an array of instrument registers. Each track has a “current instrument setting”, which is simply an index number into this array. This is like setting a raster image’s pixel to a specific color number (a reference to a color value through a “color register”) or setting a text character to a specific font number (a reference to a font through a “font register”). This is diagramed below:

“INS1” chunks in a SMUS score name the instruments to use for that score. The player program uses these names to locate instrument data.

To locate instrument data, the player performs these steps:

For each right register, check for a suitable instrument with the right name...

(“Suitable” means usable with an available output device and driver; use case independent name comparisons.)

Initialize the instrument register to point to a built-in default instrument.

(Every player program must have default instruments. Simple programs stop here. For fancier programs, the default instruments are a backstop in case the search fails.)

Check any instrument FORMs embedded in the FORM SMUS. (This is an “instrument cache”.)

Else check the default instruments.

Else search the local “instrument library”. (The library might simply be a disk directory.)

If all else fails, display the desired instrument name and ask the user to pick an available one.

This algorithm can be implemented to varying degrees of fanciness. It’s OK to stop searching after step 1, 2, 3, or 4. If exact instrument name matches fail, it’s OK to try approximate matches. E.g., search for any kind of “guitar” if you can’t find a “Spanish guitar”. In any case, a player only has to search for instruments while loading a score.

When the embedded instruments are suitable, they save the program from asking the user to insert the “right” disk in a drive and searching that disk for the “right” instrument. But it’s just a cache. In practice, we rarely move scores between environments so the cache often works. When the score is moved, embedded instruments must be discarded (a cache miss) and other instrument data used.

Be careful to distinguish an instrument’s name from its filename—the contents name vs. container name. A musical instrument FORM should contain a NAME chunk that says what instrument it really is. Its filename, on the other hand, is a handle used to locate the FORM. Filenames are affected by external factors like drives, directories, and filename character and length limits. Instrument names are not.

Issue: Consider instrument naming conventions for consistency. Consider a naming convention that aids approximate matches. E.g., we could accept “guitar, bass1” if we didn’t find “guitar, bass”. Failing that, we could accept “guitar” or any name starting with “guitar”.

If the player implements the set-instrument score event, each track can change instrument numbers while playing. That is, it can switch between the loaded instruments.

Each time a score is played, every track’s running state information must be initialized. Specifically, each track’s instrument number should be initialized to its track number. Track 1 to instrument 1, etc. It’s as if each track began with a set-instrument event.

In this way, programs that don’t implement the set-instrument event still assign an instrument to each track. The INS1 chunks imply these initial instrument settings.

MIDI Instruments

As mentioned above, A SMUS score can also ask for MIDI instruments. This is done by putting the MIDI channel and preset numbers in an INS1 chunk with the instrument name. Some programs will honor these requests while others will just find instruments by name.

MIDI Recorder and sequencer programs may simply transcribe the MIDI channel and preset commands in a recording session. For this purpose, set-MIDI-channel and set-MIDI-preset events can be embedded in a SMUS score’s tracks. Most programs should ignore these events. An editor program that wants to exchange scores with such programs should recognize these events. It should let the user change them to the more general set-instrument events.

Standard Data and Property Chunks

A FORM SMUS contains a required property “SHDR” followed by any number of parallel “track” data chunks “TRAK”. Optional property chunks such as “NAME”, copyright “(c) ”, and instrument reference “INS1” may also appear. Any of the properties may be shared over a LIST of FORMs SMUS by putting them in a PROP SMUS. [See the IFF reference.]

Required Property SHDR

The required property “SHDR” holds an SScoreHeader as defined in these C declarations and following documentation. An SHDR specifies global information for the score. It must appear before the TRAKs in a FORM SMUS.

#define ID\_SMUS MakeID('S', 'M', 'U', 'S')

#define ID\_SHDR MakeID('S', 'H', 'D', 'R')

typedef struct {

UWORD tempo; /* tempo, 128ths quarter note/minute */

UBYTE volume; /* overall playback volume 0 through 127 */

UBYTE ctTrack; /* count of tracks in the score */

} SScoreHeader;

[Implementation details. In the C struct definitions in this memo, fields are filed in the order shown. A UBYTE field is packed into an 8-bit byte. Programs should set all “pad” fields to 0. MakeID is a C macro defined in the main IFF document and in the source file IFF.h.]

The field tempo gives the nominal tempo for all tracks in the score. It is expressed in 128ths of a quarter note per minute, i.e., 1 represents 1 quarter note per 128 minutes while 12800 represents 100 quarter notes per minute. You may think of this as a fixed point fraction with a 9-bit integer part and a 7-bit fractional part (to the right of the point). A coarse-tempoed program may simply shift tempo right by 7 bits to get a whole number of quarter notes per minute. The tempo field can store tempi in the range 0 up to 512. The playback program may adjust this tempo, perhaps under user control.

Actually, this global tempo could actually be just an initial tempo if there are any “set tempo” SEvents inside the score (see TRAK, below). Or the global tempo could be scaled by “scale tempo” SEvents inside the score. These are potential extensions that can safely be ignored by current programs. [See More SEvents To Be Defined, below.]

The field volume gives an overall nominal playback volume for all tracks in the score. The range of volume values 0 through 127 is like a MIDI key velocity value. The playback program may adjust this volume, perhaps under direction of a user “volume control”.

Actually, this global volume level could be scaled by dynamic-mark SEvents inside the score (see TRAK, below).

The field ctTrack holds the count of tracks, i.e., the number of TRAK chunks in the FORM SMUS (see below). This information helps the reader prepare for the following data.

A playback program will typically load the score and call a driver routine PlayScore(tracks, tempo, volume), supplying the tempo and volume from the SHDR chunk.

Optional Text Chunks NAME, (c), AUTH, ANNO

Several text chunks may be included in a FORM SMUS to keep ancillary information.

The optional property “NAME” names the musical score, for instance “Fugue in C”.

The optional property “(c) ” holds a copyright notice for the score. The chunk ID “(c) ” serves the function of the copyright characters “©”. E.g., a “(c) ” chunk containing “1986 Electronic Arts” means “© 1986 Electronic Arts”.

The optional property “AUTH” holds the name of the score’s author.

The chunk types “NAME”, “(c) ”, and “AUTH” are property chunks. Putting more than one NAME (or other) property in a FORM is redundant. Just the last NAME counts. A property should be shorter than 256 characters. Properties can appear in a PROP SMUS to share them over a LIST of FORMs SMUS.

The optional data chunk “ANNO” holds any text annotations typed in by the author.

An ANNO chunk is not a property chunk, so you can put more than one in a FORM SMUS. You can make ANNO chunks any length up to 2^31 - 1 characters, but 32767 is a practical limit. Since they’re not properties, ANNO chunks don’t belong in a PROP SMUS. That means they can’t be shared over a LIST of FORMs SMUS.

Syntactically, each of these chunks contains an array of 8-bit ASCII characters in the range “ ” (SP, hex 20) through “~” (tilde, hex 7F), just like a standard “TEXT” chunk. [See “Strings, String Chunks, and String Properties” in “EA IFF 85” Electronic Arts Interchange File Format.] The chunk’s ckSize field holds the count of characters.

#define ID\_NAME MakeID('N', 'A', 'M', 'E')

/* NAME chunk contains a CHAR[], the musical score's name. */

#define ID\_Copyright MakeID('(', 'c', ')', ' ')

/* "(c) " chunk contains a CHAR[], the FORM's copyright notice. */

#define ID\_AUTH MakeID('A', 'U', 'T', 'H')

/* AUTH chunk contains a CHAR[], the name of the score's author. */

#define ID\_ANNO MakeID('A', 'N', 'N', 'O')

/* ANNO chunk contains a CHAR[], author's text annotations. */

Remember to store a 0 pad byte after any odd-length chunk.

Optional Property INS1

The “INS1” chunks in a FORM SMUS identify the instruments to use for this score. A program can ignore INS1 chunks and stick with its built-in default instrument assignments. Or it can use them to locate instrument data. [See “Instrument Registers” in section 2, above.]

#define ID\_INS1 MakeID('I', 'N', 'S', '1')

/* Values for the RefInstrument field "type". */

#define INS1\_Name 0 /* just use the name; ignore data1, data2 */

#define INS1\_MIDI 1 /* <data1, data2> = MIDI <channel, preset> */

typedef struct {

UBYTE register; /* set this instrument register number */

UBYTE type; /* instrument reference type */

UBYTE data1, data2; /* depends on the "type" field */

CHAR name[]; /* instrument name */

} RefInstrument;

An INS1 chunk names the instrument for instrument register number register. The register field can range from 0 through 255. In practice, most scores will need only a few instrument registers.

The name field gives a text name for the instrument. The string length can be determined from the ckSize of the INS1 chunk. The string is simply an array of 8-bit ASCII characters in the range “ ” (SP, hex 20) through “~” (tilde, hex 7F).

Besides the instrument name, an INS1 chunk has two data numbers to help locate an instrument. The use of these data numbers is controlled by the type field. A value type = INS1_Name means just find an instrument by name. In this case, data1 and data2 should just be set to 0. A value type = INS1_MIDI means look for an instrument on MIDI channel # data1, preset # data2. Programs and computers without MIDI outputs will just ignore the MIDI data. They’ll always look for the named instrument. Other values of the type field are reserved for future standardization.

See section 2, above, for the algorithm for locating instrument data by name.

Obsolete Property INST

The chunk type “INST” is obsolete in SMUS. It was revised to form the “INS1” chunk.

Data Chunk TRAK

The main contents of a score is stored in one or more TRAK chunks representing parallel “tracks”. One TRAK chunk per track.

The contents of a TRAK chunk is an array of 16-bit “events” such as “note”, “rest”, and “set instrument”. Events are really commands to a simple scheduler, stored in time order. The tracks can be polyphonic, that is, they can contain chorded “note” events.

Each event is stored as an “SEvent” record. (“SEvent” means “simple musical event”.) Each SEvent has an 8-bit type field called an “sID” and 8 bits of type-dependent data. This is like a machine language instruction with an 8-bit opcode and an 8-bit operand.

This format is extensible since new event types can be defined in the future. The “note” and “rest” events are the only ones that every program must understand. We will carefully design any new event types so that programs can safely skip over unrecognized events in a score.

Caution: ID codes must be allocated by a central clearinghouse to avoid conflicts. The AmigaOS development team provides this clearinghouse service.

Here are the C type definitions for TRAK and SEvent and the currently defined sID values. Afterward are details on each SEvent.

#define ID\_TRAK MakeID('T', 'R', 'A', 'K')

/* TRAK chunk contains an SEvent[]. */

/* SEvent: Simple musical event. */

typedef struct {

UBYTE sID; /* SEvent type code */

UBYTE data; /* sID-dependent data */

} SEvent;

/* SEvent type codes "sID". */

#define SID\_FirstNote 0

#define SID\_LastNote 127 /* sIDs in the range SID\_FirstNote through

* SID\_LastNote (sign bit = 0) are notes.

* The sID is the MIDI tone number (pitch).*/

#define SID\_Rest 128 /* a rest (same data format as a note). */

#define SID\_Instrument 129 /* set instrument number for this track. */

#define SID\_TimeSig 130 /* set time signature for this track. */

#define SID\_KeySig 131 /* set key signature for this track. */

#define SID\_Dynamic 132 /* set volume for this track. */

#define SID\_MIDI\_Chnl 133 /* set MIDI channel number (sequencers) */

#define SID\_MIDI\_Preset 134 /* set MIDI preset number (sequencers) */

#define SID\_Clef 135 /* inline clef change.

* 0=Treble, 1=Bass, 2=Alto, 3=Tenor.(new) */

#define SID\_Tempo 136 /* Inline tempo in beats per minute.(new) */

/* SID values 144 through 159: reserved for Instant Music SEvents. */

/* Remaining sID values up through 254: reserved for future

* standardization. */

#define SID\_Mark 255 /* sID reserved for an end-mark in RAM. */

Note and Rest SEvents

The note and rest SEvents SID_FirstNote through SID_Rest have the following structure overlaid onto the SEvent structure:

typedef struct {

UBYTE tone; /* MIDI tone number 0 to 127; 128 = rest */

unsigned chord :1, /* 1 = a chorded note */

tieOut :1, /* 1 = tied to the next note or chord */

nTuplet :2, /* 0 = none, 1 = triplet, 2 = quintuplet,

* 3 = septuplet */

dot :1, /* dotted note; multiply duration by 3/2 */

division :3; /* basic note duration is 2^-division: 0 =

* whole note, 1 = half note, 2 = quarter

* note, .... 7 = 128th note */

} SNote;

[Implementation details. Unsigned “:n” fields are packed into n bits in the order shown, most significant bit to least significant bit. An SNote fits into 16 bits like any other SEvent. Warning: Some compilers don’t implement bit-packed fields properly. E.g., Lattice 68000 C pads a group of bit fields out to a LONG, which would make SNote take 5-bytes! In that situation, use the bit-field constants defined below.]

The SNote structure describes one “note” or “rest” in a track. The field SNote.tone, which is overlaid with the SEvent.sID field, indicates the MIDI tone number (pitch) in the range 0 through 127. A value of 128 indicates a rest.

The fields nTuplet, dot, and division together give the duration of the note or rest. The division gives the basic duration: whole note, half note, etc. The dot indicates if the note or rest is dotted. A dotted note is 3/2 as long as an undotted note. The value nTuplet (0 through 3) tells if this note or rest is part of an N-tuplet of order 1 (normal), 3, 5, or 7; an N-tuplet of order (2 * nTuplet + 1). A triplet note is 2/3 as long as a normal note, while a quintuplet is 4/5 as long and a septuplet is 6/7 as long.

Putting these three fields together, the duration of the note or rest is

`="202D 4.5em 2^{- division} * \{ 1, 3/2\} * \{ 1, 2/3, 4/5, 6/7\}

These three fields are contiguous so you can easily convert to your local duration encoding by using the combined 6 bits as an index into a mapping table.

The field chord indicates if the note is chorded with the following note (which is supposed to have the same duration). A group of notes may be chorded together by setting the chord bit of all but the last one. (In the terminology of SSSP and GSCR, setting the chord bit to 1 makes the “entry delay” 0.) A monophonic-track player can simply ignore any SNote event whose chord bit is set, either by discarding it when reading the track or by skipping it when playing the track.

Programs that create polyphonic tracks are expected to store the most important note of each chord last, which is the note with the 0 chord bit. This way, monophonic programs will play the most important note of the chord. The most important note might be the chord’s root note or its melody note.

If the field tieOut is set, the note is tied to the following note in the track if the following note has the same pitch. A group of tied notes is played as a single note whose duration is the sum of the component durations. Actually, the tie mechanism ties a group of one or more chorded notes to another group of one or more chorded notes. Every note in a tied chord should have its tieOut bit set.

Of course, the chord and tieOut fields don’t apply to SID_Rest SEvents.

Programs should be robust enough to ignore an unresolved tie, i.e., a note whose tieOut bit is set but isn’t followed by a note of the same pitch. If that’s true, monophonic-track programs can simply ignore chorded notes even in the presense of ties. That is, tied chords pose no extra problems.

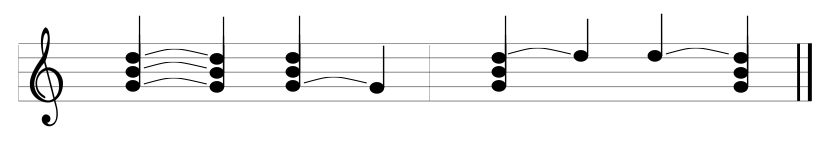

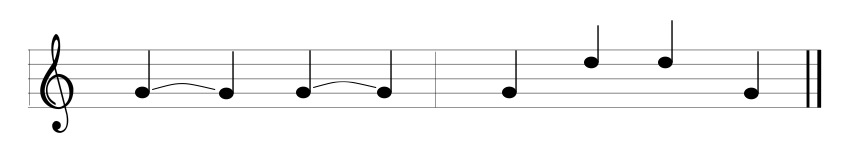

The following diagram shows some combinations of notes and chords tied to notes and chords. The text below the staff has a column for each SNote SEvent to show the pitch, chord bit, and tieOut bit.

A treble staff with chords and ties:

Corresponding SNote values in the TRAK chunk:

Pitch: D B G D B G D B G G D B G B B D B G chord: c c - c c - c c - - c c - - - c c - tieOut: t t t - - - t t t - t t t - t - - -

If you read the above track into a monophonic-track program, it’ll strip out the chorded notes and ignore unresolved ties. You’ll end up with:

Pitch: G G G G G B B G chord: - - - - - - - - tieOut: t - t - (t) - (t) -

A rest event (sID = SID_Rest) has the same SEvent.data field as a note. It tells the duration of the rest. The chord and tieOut fields of rest events are ignored.

Within a TRAK chunk, note and rest events appear in time order.

Instead of the bit-packed structure SNote, it might be easier to assemble data values by or-ing constants and to disassemble them by masking and shifting. In that case, use the following definitions.

#define noteChord (1<<7) /* note is chorded to next note */ #define noteTieOut (1<<6) /* tied to next note/chord */ #define noteNShift 4 /* shift count for nTuplet field */ #define noteN3 (1<<noteNShift) /* note is a triplet */ #define noteN5 (2<<noteNShift) /* note is a quintuplet */ #define noteN7 (3<<noteNShift) /* note is a septuplet */ #define noteNMask noteN7 /* bit mask for the nTuplet field */ #define noteDot (1<<3) /* note is dotted */ #define noteD1 0 /* whole note division */ #define noteD2 1 /* half note division */ #define noteD4 2 /* quarter note division */ #define noteD8 3 /* eighth note division */ #define noteD16 4 /* sixteenth note division */ #define noteD32 5 /* thirty-secondth note division */ #define noteD64 6 /* sixty-fourth note division */ #define noteD128 7 /* 1/128 note division */ #define noteDMask noteD128 /* bit mask for the division field */ #define noteDurMask 0x3F /* mask for combined duration fields*/

Note: The remaining SEvent types are optional. A writer program doesn’t have to generate them. A reader program can safely ignore them.

Set Instrument SEvent

One of the running state variables of every track is an instrument number. An instrument number is the array index of an “instrument register”, which in turn points to an instrument. (See “Instrument Registers”, in section 2.) This is like a color number in a bitmap; a reference to a color through a “color register”.

The initial setting for each track’s instrument number is the track number. Track 1 is set to instrument 1, etc. Each time the score is played, every track’s instrument number should be reset to the track number.

The SEvent SID_Instrument changes the instrument number for a track, that is, which instrument plays the following notes. Its SEvent.data field is an instrument register number in the range 0 through 255. If a program doesn’t implement the SID_Instrument event, each track is fixed to one instrument.

Set Time Signature SEvent

The SEvent SID_TimeSig sets the time signature for the track. A “time signature” SEvent has the following structure overlaid on the SEvent structure:

typedef struct {

UBYTE type; /* = SID\_TimeSig */

unsigned timeNSig :5, /* time sig. "numerator" is timeNSig + 1 */

timeDSig :3; /* time sig. "denominator" is 2^timeDSig:*

* 0 = whole note, 1 = half note, 2 = *

* quarter note,....7 = 128th note */

} STimeSig;

[Implementation details. Unsigned “:n” fields are packed into n bits in the order shown, most significant bit to least significant bit. An STimeSig fits into 16 bits like any other SEvent. Warning: Some compilers don’t implement bit-packed fields properly. E.g., Lattice C pads a group of bit fields out to a LONG, which would make an STimeSig take 5-bytes! In that situation, use the bit-field constants defined below.]

The field type contains the value SID_TimeSig, indicating that this SEvent is a “time signature” event. The field timeNSig indicates the time signature “numerator” is timeNSig + 1, that is, 1 through 32 beats per measure. The field timeDSig indicates the time signature “denominator” is 2^timeDSig, that is each “beat” is a `="202D 2^-timeDSig note (see SNote division, above). So 4/4 time is expressed as timeNSig = 3, timeDSig = 2.

The default time signature is 4/4 time. Be aware that the time signature has no effect on the score’s playback. Tempo is uniformly expressed in quarter notes per minute, independent of time signature. (Quarter notes per minute would equal beats per minute only if timeDSig = 2, n/4 time). Nonetheless, any program that has time signatures should put them at the beginning of each TRAK when creating a FORM SMUS because music editors need them.

Instead of the bit-packed structure STimeSig, it might be easier to assemble data values by or-ing constants and to disassemble them by masking and shifting. In that case, use the following definitions.

#define timeNMask 0xF8 /* bit mask for the timeNSig field */ #define timeNShift 3 /* shift count for timeNSig field */ #define timeDMask 0x07 /* bit mask for the timeDSig field */

Key Signature SEvent

An SEvent SID_KeySig sets the key signature for the track. Its data field is a UBYTE number encoding a major key:

data key music notation data key music notation 0 C maj 1 G # 8 F b 2 D ## 9 Bb bb 3 A ### 10 Eb bbb 4 E #### 11 Ab bbbb 5 B ##### 12 Db bbbbb 6 F# ###### 13 Gb bbbbbb 7 C# ####### 14 Cb bbbbbbb

A SID_KeySig SEvent changes the key for the following notes in that track. C major is the default key in every track before the first SID_KeySig SEvent.

Dynamic Mark SEvent

An SEvent SID_Dynamic represents a dynamic mark like ppp and fff in Common Music Notation. Its data field is a MIDI key velocity number 0 through 127. This sets a “volume control” for following notes in the track. This “track volume control” is scaled by the overall score volume in the SHDR chunk. The default dynamic level is 127 (full volume).

Set MIDI Channel SEvent

The SEvent SID_MIDI_Chnl is for recorder programs to record the set-MIDI-channel low level event. The data byte contains a MIDI channel number. Other programs should use instrument registers instead.

Set MIDI Preset SEvent

The SEvent SID_MIDI_Preset is for recorder programs to record the set-MIDI-preset low level event. The data byte contains a MIDI preset number. Other programs should use instrument registers instead.

Instant Music Private SEvents

Sixteen SEvents are used for private data for the Instant Music program. SID values 144 through 159 are reserved for this purpose. Other programs should skip over these SEvents.

End-Mark SEvent

The SEvent type SID_Mark is reserved for an end marker in working memory. This event is never stored in a file. It may be useful if you decide to use the filed TRAK format intact in working memory.

More SEvents To Be Defined

More SEvent can be defined in the future. The sID codes 133 through 143 and 160 through 254 are reserved for future needs. Caution: sID codes must be allocated by a central “clearinghouse” to avoid conflicts.

The following SEvent types are under consideration and should not yet be used.

Issue: A “change tempo” SEvent changes tempo during a score. Changing the tempo affects all tracks, not just the track containing the change tempo event.

One possibility is a “scale tempo” SEvent SID_ScaleTempo that rescales the global tempo:

currentTempo := globalTempo * (data + 1) / 128

This can scale the global tempo (in the SHDR) anywhere from <math>\times ^{1}/\_{128}</math> to <math>\times 2</math> in roughly 1% increments.

An alternative is two events SID_SetHTempo and SID_SetLTempo.SID_SetHTempo gives the high byte and SID_SetLTempo gives the low byte of a new tempo setting, in 128ths quarter note/minute. SetHTempo automatically sets the low byte to 0, so the SetLTempo event isn’t needed for coarse settings. In this scheme, the SHDR’s tempo is simply a starting tempo.

An advantage of SID_ScaleTempo is that the playback program can just alter the global tempo to adjust the overall performance time and still easily implement tempo variations during the score. But the “set tempo” SEvent may be simpler to generate.

Issue: The events SID_BeginRepeat and SID_EndRepeat define a repeat span for one track. The span of events between a BeginRepeat and an EndRepeat is played twice. The SEvent.data field in the BeginRepeat event could give an iteration count, 1 through 255 times or 0 for “repeat forever”.

Repeat spans can be nested. All repeat spans automatically end at the end of the track.

An event SID_Ending begins a section like “first ending” or "second ending". The SEvent.data field gives the ending number. This SID_Ending event only applies to the innermost repeat group. (Consider generalizing it.)

A more general alternative is a “subtrack” or “subscore” event. A “subtrack” event is essentially a “subroutine call” to another series of SEvents. This is a nice way to encode all the possible variations of repeats, first endings, codas, and such.

To define a subtrack, we must demark its start and end. One possibility is to define a relative branch-to-subtrack event SID_BSR and a return-from-subtrack event SID_RTS. The 8-bit data field in the SID_BSR event can reach as far as 512 SEvents. A second possibility is to call a subtrack by index number, with an IFF chunk outside the TRAK defining the start and end of all subtracks. This is very general since a portion of one subtrack can be used as another subtrack. It also models the tape recording practice of first “laying down a track” and then selecting portions of it to play and repeat. To embody the music theory idea of playing a sequence like “ABBA”, just compose the “main” track entirely of subtrack events. A third possibility is to use a numbered subtrack chunk “STRK” for each subroutine.

Private Chunks

As in any IFF FORM, there can be private chunks in a FORM SMUS that are designed for one particular program to store its private information. All IFF reader programs skip over unrecognized chunks, so the presense of private chunks can’t hurt.

Instant Music stores some global score information in a chunk of ID “IRev” and some other information in a chunk of ID “BIAS”.

Appendix A. Quick Reference

Type Definitions

Here’s a collection of the C type definitions in this memo. In the “struct” type definitions, fields are filed in the order shown. A UBYTE field is packed into an 8-bit byte. Programs should set all “pad” fields to 0.

#define ID\_SMUS MakeID('S', 'M', 'U', 'S')

#define ID\_SHDR MakeID('S', 'H', 'D', 'R')

typedef struct {

UWORD tempo; /* tempo, 128ths quarter note/minute */

UBYTE volume; /* overall playback volume 0 through 127 */

UBYTE ctTrack; /* count of tracks in the score */

} SScoreHeader;

#define ID\_NAME MakeID('N', 'A', 'M', 'E')

/* NAME chunk contains a CHAR[], the musical score's name. */

#define ID\_Copyright MakeID('(', 'c', ')', ' ')

/* "(c) " chunk contains a CHAR[], the FORM's copyright notice. */

#define ID\_AUTH MakeID('A', 'U', 'T', 'H')

/* AUTH chunk contains a CHAR[], the name of the score's author. */

#define ID\_ANNO MakeID('A', 'N', 'N', 'O')

/* ANNO chunk contains a CHAR[], author's text annotations. */

#define ID\_INS1 MakeID('I', 'N', 'S', '1')

/* Values for the RefInstrument field "type". */

#define INS1\_Name 0 /* just use the name; ignore data1, data2 */

#define INS1\_MIDI 1 /* <data1, data2> = MIDI <channel, preset> */

typedef struct {

UBYTE register; /* set this instrument register number */

UBYTE type; /* instrument reference type */

UBYTE data1, data2; /* depends on the "type" field */

CHAR name[]; /* instrument name */

} RefInstrument;

#define ID\_TRAK MakeID('T', 'R', 'A', 'K')

/* TRAK chunk contains an SEvent[]. */

/* SEvent: Simple musical event. */

typedef struct {

UBYTE sID; /* SEvent type code */

UBYTE data; /* sID-dependent data */

} SEvent;

/* SEvent type codes "sID". */

#define SID\_FirstNote 0

#define SID\_LastNote 127 /* sIDs in the range SID\_FirstNote through

* SID\_LastNote (sign bit = 0) are notes. The

* sID is the MIDI tone number (pitch). */

#define SID\_Rest 128 /* a rest (same data format as a note). */

#define SID\_Instrument 129 /* set instrument number for this track.*/

#define SID\_TimeSig 130 /* set time signature for this track. */

#define SID\_KeySig 131 /* set key signature for this track. */

#define SID\_Dynamic 132 /* set volume for this track. */

#define SID\_MIDI\_Chnl 133 /* set MIDI channel number (sequencers) */

#define SID\_MIDI\_Preset 134 /* set MIDI preset number (sequencers) */

#define SID\_Clef 135 /* inline clef change. *

* 0=Treble, 1=Bass, 2=Alto, 3=Tenor. */

#define SID\_Tempo 136 /* Inline tempo in beats per minute. */

/* SID values 144 through 159: reserved for Instant Music SEvents. */

/* Remaining sID values up through 254: reserved for future

* standardization. */

#define SID\_Mark 255 /* sID reserved for an end-mark in RAM. */

/* SID\_FirstNote..SID\_LastNote, SID\_Rest SEvents */

typedef struct {

UBYTE tone; /* MIDI tone number 0 to 127; 128 = rest */

unsigned chord :1, /* 1 = a chorded note */

tieOut :1, /* 1 = tied to the next note or chord */

nTuplet :2, /* 0 = none, 1 = triplet, 2 = quintuplet,

* 3 = septuplet */

dot :1, /* dotted note; multiply duration by 3/2 */

division :3; /* basic note duration is 2-division: 0 = whole

* note, 1 = half note, 2 = quarter note,

* 7 = 128th note */

} SNote;

#define noteChord (1<<7) /* note is chorded to next note */

#define noteTieOut (1<<6) /* tied to next note/chord */

#define noteNShift 4 /* shift count for nTuplet field */

#define noteN3 (1<<noteNShift) /* note is a triplet */

#define noteN5 (2<<noteNShift) /* note is a quintuplet */

#define noteN7 (3<<noteNShift) /* note is a septuplet */

#define noteNMask noteN7 /* bit mask for the nTuplet field */

#define noteDot (1<<3) /* note is dotted */

#define noteD1 0 /* whole note division */

#define noteD2 1 /* half note division */

#define noteD4 2 /* quarter note division */

#define noteD8 3 /* eighth note division */

#define noteD16 4 /* sixteenth note division */

#define noteD32 5 /* thirty-secondth note division */

#define noteD64 6 /* sixty-fourth note division */

#define noteD128 7 /* 1/128 note division */

#define noteDMask noteD128 /* bit mask for the division field */

#define noteDurMask 0x3F /* mask for combined duration fields */

/* SID\_Instrument SEvent */

/* "data" value is an instrument register number 0 through 255. */

/* SID\_TimeSig SEvent */

typedef struct {

UBYTE type; /* = SID\_TimeSig */

unsigned timeNSig :5, /* time sig. "numerator" is timeNSig + 1 */

timeDSig :3; /* time sig. "denominator" is 2^timeDSig: *

* 0 = whole note, 1 = half note, 2 = *

* quarter note,.... 7 = 128th note */

} STimeSig;

#define timeNMask 0xF8 /* bit mask for the timeNSig field */

#define timeNShift 3 /* shift count for timeNSig field */

#define timeDMask 0x07 /* bit mask for the timeDSig field */

/* SID\_KeySig SEvent */

/* "data" value 0 = Cmaj; 1 through 7 = G,D,A,E,B,F#,C#; *

* 8 through 14 = F,Bb,Eb,Ab,Db,Gb,Cb. */

/* SID\_Dynamic SEvent */

/* "data" value is a MIDI key velocity 0..127. */

SMUS Regular Expression

Here’s a regular expression summary of the FORM SMUS syntax. This could be an IFF file or part of one.

SMUS ::= "FORM" #{ "SMUS" SHDR [NAME] [Copyright] [AUTH] [IRev]

ANNO* INS1* TRAK* InstrForm* }

SHDR ::= "SHDR" #{ SScoreHeader }

NAME ::= "NAME" #{ CHAR* } [0]

Copyright ::= "(c) " #{ CHAR* } [0]

AUTH ::= "AUTH" #{ CHAR* } [0]

IRev ::= "IRev" #{ ... }

ANNO ::= "ANNO" #{ CHAR* } [0]

INS1 ::= "INS1" #{ RefInstrument } [0]

TRAK ::= "TRAK" #{ SEvent* }

InstrForm ::= "FORM" #{ ... }

The token “#” represents a ckSize LONG count of the following <math>\{</math>braced<math>\}</math> data bytes. Literal items are shown in “quotes”, [square bracket items] are optional, and “*” means 0 or more replications. A sometimes-needed pad byte is shown as “[0]”.

Actually, the order of chunks in a FORM SMUS is not as strict as this regular expression indicates. The SHDR, NAME, Copyright, AUTH, IRev, ANNO, and INS1 chunks may appear in any order, as long as they precede the TRAK chunks.

The chunk “InstrForm” represents any kind of instrument data FORM embedded in the FORM SMUS. For example, see the document “8SVX” IFF 8-Bit Sampled Voice. Of course, a recipient program will ignore an instrument FORM if it doesn’t recognize that FORM type.

Appendix B. SMUS Example

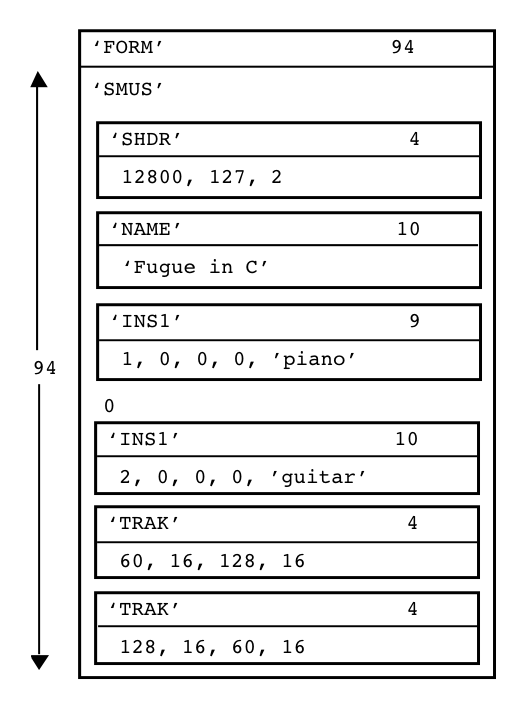

Here’s a box diagram for a simple example, a SMUS with two instruments and two tracks. Each track contains 1 note event and 1 rest event.

The “0” after the first INS1 chunk is a pad byte.

Appendix C. Standards Committee

The following people contributed to the design of this SMUS standard:

Ralph Bellafatto, Cherry Lane Technologies

Geoff Brown, Uhuru Sound Software

Steve Hayes, Electronic Arts

Jerry Morrison, Electronic Arts