Copyright (c) Hyperion Entertainment and contributors.

Classic Graphics Primitives

Display Routines and Structures

| Caution |

|---|

| This section describes the lowest-level graphics interface to the system hardware. If you use any of the routines and the data structures described in these sections, your program will essentially take over the entire display. In general, this is not compatible with Intuition’s multiwindow operating environment since Intuition calls these low-level routines for you. |

The descriptions of the display routines, as well as those of the drawing routines, occasionally use the same terminology as that in the Intuition chapters. These routines and data structures are the same ones that Intuition software uses to produce its displays.

The computer produces a display from a set of instructions you define. You organize the instructions as a set of parameters known as the View structure (see the <graphics/view.h> include file for more information).

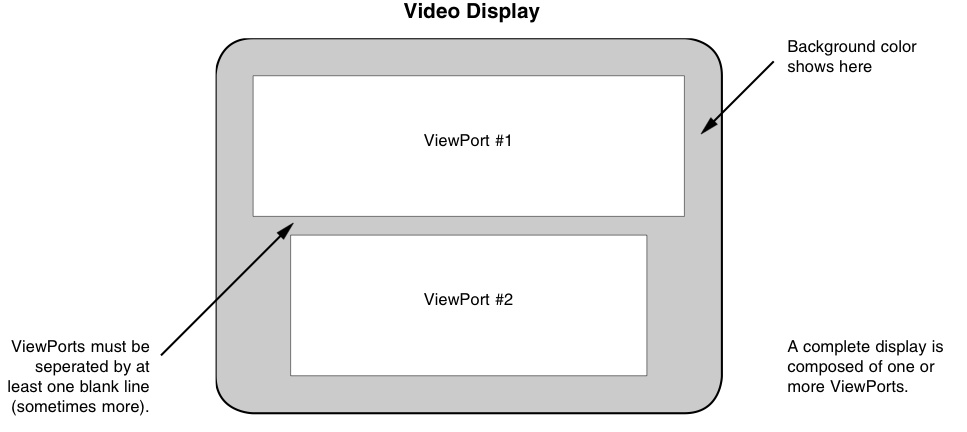

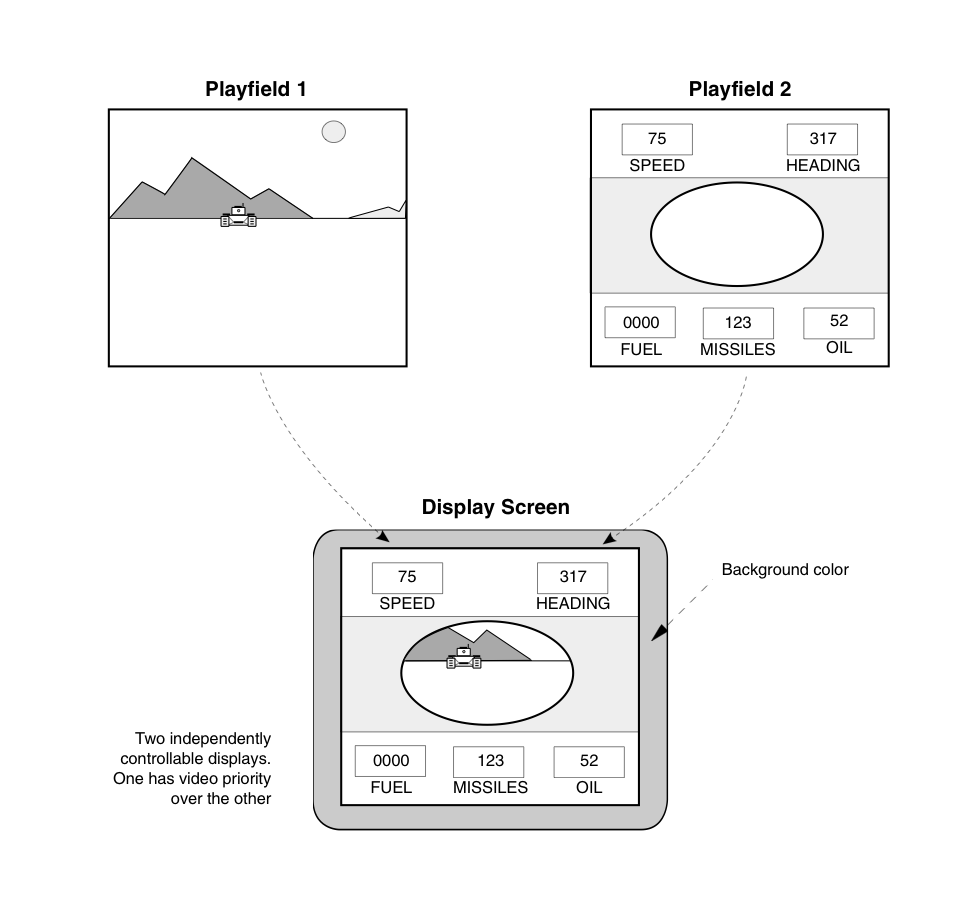

The following figure shows how the system interprets the contents of a View structure. This drawing shows a complete display composed of two different component parts, which could (for example) be a low-resolution, multicolored part and a high-resolution, two-colored part.

Figure 27-9: The Display Is Composed of ViewPorts

A complete display consists of one or more ViewPorts, whose display sections are vertically separated from each other by at least one blank scan line (non-interlaced). (If the system must make many changes to the display during the transition from one ViewPort to the next, there may be two or more blank scanlines between the ViewPorts.)

The viewable area defined by each ViewPort is rectangular. It may be only a portion of the full ViewPort, it may be the full ViewPort, or it may be larger than the full ViewPort, allowing it to be moved within the limits of its DisplayClip (discussed later). You are essentially defining a display consisting of a number of stacked rectangular areas in which separate sections of graphics rasters can be shown.

Limitations on the Use of Viewports

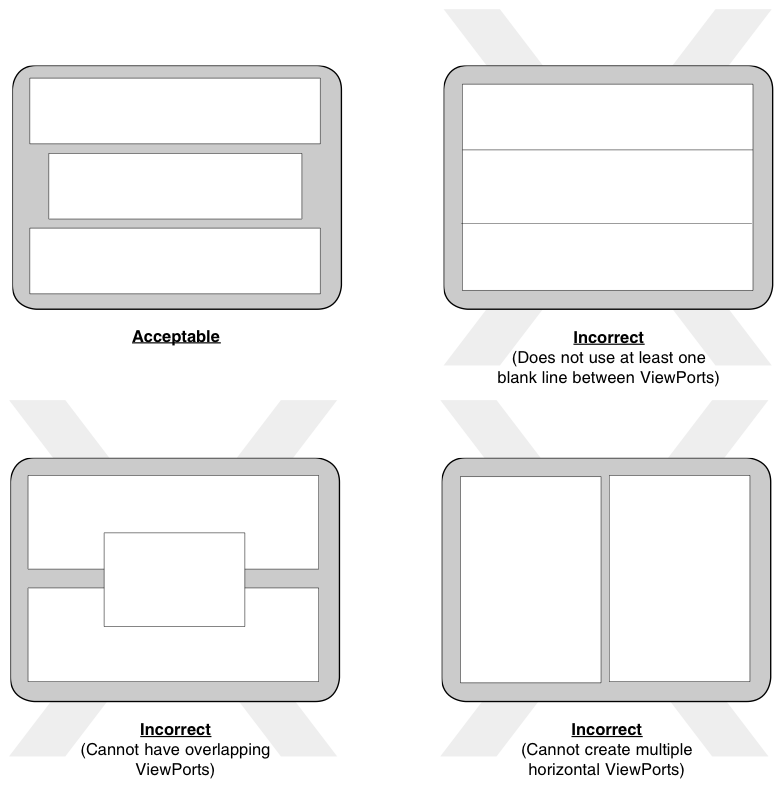

The system software for defining ViewPorts allows only vertically stacked fields to be defined.

The following figure shows acceptable and unacceptable display configurations.

Figure 27-10: Correct and Incorrect Uses of ViewPorts

A ViewPort is related to the custom screen option of Intuition. In a custom screen, you can split the screen into slices as shown in the “correct” illustration of the above figure. Each custom screen can have its own set of colors, use its own resolution, and show its own display area.

Characteristics of a ViewPort

To describe a ViewPort fully, you need to set the following parameters: height, width, depth and display mode.

In addition to these parameters, you must tell the system the location in memory from which the data for the ViewPort display should be retrieved (by associating with it a BitMap structure) and how to position the final ViewPort display on the screen. The ViewPort will take on the user’s default Workbench colors unless otherwise instructed with a ColorMap. See the section called “Preparing the ColorMap Structure” for more information.

ViewPort Size Specifications

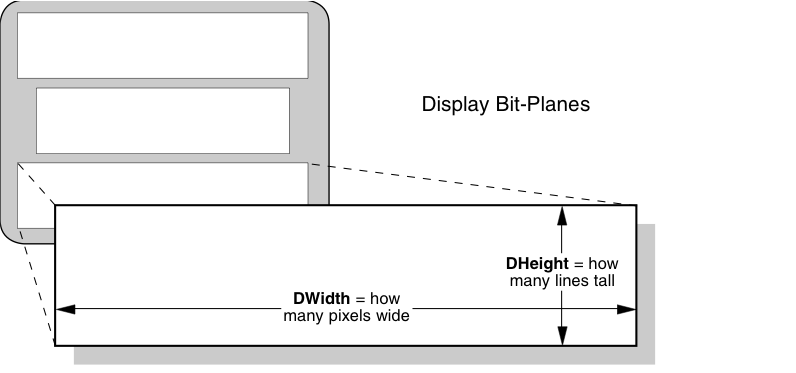

The following figure illustrates that the variables DHeight, and DWidth specify the size of a ViewPort.

Figure 27-11: Size Definition for a ViewPort

ViewPort Height

The DHeight field of the ViewPort structure determines how many video lines will be reserved to show the height of this display segment. The size of the actual segment depends on whether you define a non-interlaced or an interlaced display. An interlaced ViewPort displays twice as many lines as does a non-interlaced ViewPort in the same physical height.

For example, a complete View consisting of two ViewPorts might be defined as follows:

ViewPort

1 is 150 lines, high-resolution mode (uses the top three-quarters of the display).

ViewPort

2 is 49 lines of low-resolution mode (uses the bottom quarter of the display and allows the space for the required blank line between ViewPorts).

Initialize the height directly in DHeight. Nominal height for a non-interlaced display is 200 lines for NTSC, 256 for PAL. Nominal height for an interlaced display is 400 lines for NTSC, 512 for PAL.

To set your ViewPort to the maximum supported (displayable) height, use the following code fragment:

struct DimensionInfo querydims;

struct Rectangle *oscan;

struct ViewPort viewport;

if (GetDisplayInfoData( NULL,(UBYTE *)&querydims, sizeof(struct DimensionInfo),

DTAG_DIMS, modeID ))

{

/* Use StdOScan instead of MaxOScan to get standard overscan */

/* dimensions as set by the user in Overscan Preferences */

oscan = &querydims.MaxOScan;

viewPort->DHeight = oscan->MaxY - oscan->MinY + 1;

}

ViewPort Width

The DWidth variable in the ViewPort structure determines how wide, in pixels, the display segment will be. To set your ViewPort to the maximum supported (displayable) NTSC high-resolution width, use the following fragment:

struct DimensionInfo querydims;

struct Rectangle *oscan;

struct ViewPort viewport;

/* Use PAL_MONITOR_ID instead of NTSC_MONITOR_ID to get PAL dimensions */

if (GetDisplayInfoData( NULL,(UBYTE *)&querydims, sizeof(querydims),

DTAG_DIMS, NTSC_MONITOR_ID|HIRES_KEY ))

{

/* Use StdOScan instead of MaxOScan to get standard overscan */

/* dimensions as set by the user in Overscan Preferences */

oscan = &querydims.MaxOScan;

viewPort->DWidth = oscan->MaxX - oscan->MinX + 1;

}

You may specify a smaller value of pixels per line to produce a narrower display segment or simply set ViewPort.DWidth to the nominal value for this resolution.

Although the system software allows you define low-resolution displays as wide as 362 pixels and high-resolution displays as wide as 724 pixels, you should use caution in exceeding the normal values of 320 or 640, respectively. Because display overscan varies from one monitor to another, many video displays will not be able to show all of a wider display, and sprite display may also be affected. However, if you use the standard overscan values (DimensionInfo.StdOScan) provided by the function GetDisplayInfoData() as shown above, the user’s preference for the size of the display will be satisfied.

If you are using hardware sprites or VSprites with your display, and you specify ViewPort widths exceeding 320 or 640 pixels (for low or high-resolution, respectively), it is likely that some hardware sprites will not be properly rendered on the screen.

These sprites may not be rendered because playfield DMA (direct memory access) takes precedence over sprite DMA when an extra-wide display is produced. See the Amiga Hardware Reference Manual for a more complete description of this phenomenon.

ViewPort Color Selection

The maximum number of colors that a ViewPort can display is determined by the depth of the BitMap that the ViewPort displays. The depth is specified when the BitMap is initialized.

See the section below called “Preparing the BitMap Structure.”

Depth determines the number of bitplanes used to define the colors of the rectangular image you are trying to build (the raster image) and the number of different colors that can be displayed at the same time within a ViewPort.

For any single pixel, the system can display any one of 4,096 possible colors.

The following table shows depth values and the corresponding number of possible colors for each value.

| Colors | Depth Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | |

| 4 | 2 | |

| 8 | 3 | 1 |

| 16 | 4 | 1, 2 |

| 32 | 5 | 1, 2, 3 |

| 16 | 6 | 1, 4 |

| 64 | 6 | 1, 2, 3, 5 |

| 4,096 | 6 | 1, 2, 3, 6 |

Notes:

- Not available for SUPERHIRES.

- Single-playfield mode only - DUALPF not one of the ViewPort’s attributes.

- Low-resolution mode only - neither HIRES nor SUPERHIRES one of the ViewPort attributes.

- Dual Playfield mode - DUALPF is an attribute of this ViewPort. Up to eight colors (in three planes) for each playfield.

- Extra-Half-Brite mode - EXTRA_HALFBRITE is an attribute of this ViewPort.

- Hold-And-Modify mode only - HAM is an attribute of this ViewPort.

The color palette used by a ViewPort is specified in a ColorMap. See the section called “Preparing the ColorMap” for more information.

Depending on whether single- or dual-playfield mode is used, the system will use different color register groupings for interpreting the on-screen colors. The table below details how the depth and the different ViewPort modes affect the registers the system uses.

| Color | Depth | Registers Used |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0,1 | |

| 2 | 0-3 | |

| 3 | 0-7 | |

| 4 | 0-15 | |

| 5 | 0-31 | (if EXTRA_HALFBRITE is an attribute of this ViewPort.) |

| 6 | 0-31 | (if HAM is an attribute of this ViewPort.) |

The following table shows the five possible combinations when DUALPF is an attribute of the ViewPort.

| Depth (PF-1} | Color Registers | Depth (PF-2) | Color Registers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0,1 | 1 | 8,9 |

| 2 | 0-3 | 1 | 8,9 |

| 2 | 0-3 | 2 | 8-11 |

| 3 | 0-7 | 2 | 8-11 |

| 3 | 0-7 | 3 | 8-15 |

ViewPort Display Modes

The system has many different display modes that you can specify for each ViewPort. Under 1.3, the eight constants that control the modes are DUALPF, PFBA, HIRES, SUPERHIRES, LACE, HAM, SPRITES, and EXTRA_HALFBRITE. Some, but not all of the modes can be combined in a ViewPort. HIRES and LACE combine to make a high-resolution, interlaced ViewPort, but HIRES and SUPERHIRES conflict, and cannot be combined.

Set the display mode for a ViewPort by using the VideoControl() function as described in the section on “Monitors, Modes and the Display Database” later in this chapter.

The DUALPF and PFBA modes are related. DUALPF tells the system to treat the raster specified by this ViewPort as the first of two independent and separately controllable playfields. It also modifies the manner in which the pixel colors are selected for this raster (see the above table).

When PFBA is specified, it indicates that the second playfield has video priority over the first one. Playfield relative priorities can be controlled when the playfield is split into two overlapping regions. Single-playfield and dual-playfield modes are discussed in “Advanced Topics” below.

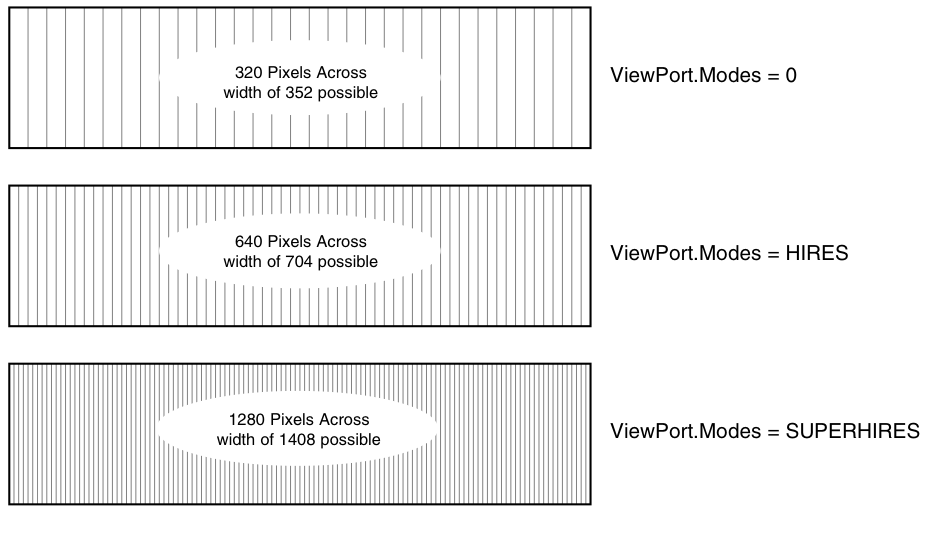

HIRES tells the system that the raster specified by this ViewPort is to be displayed with (nominally) 640 horizontal pixels, rather than the 320 horizontal pixels of Lores mode.

SUPERHIRES tells the system that the raster specified by this ViewPort is to be displayed with (nominally) 1,280 horizontal pixels. This can be used with 31 kHz scan rates to provide the VGA and Productivity modes. SUPERHIRES modes require ECS. See the section on “Determining Chip Versions” earlier in this chapter for an explanation of how to find out if the ECS is present.

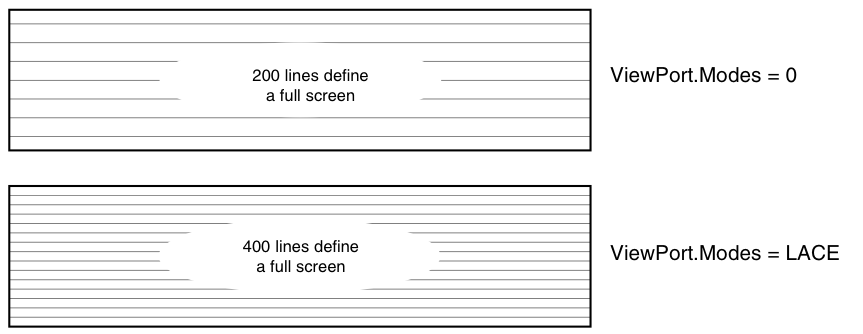

LACE tells the system that the raster specified by this ViewPort is to be displayed in interlaced mode. If the ViewPort is non-interlaced and the View is interlaced, the ViewPort will be displayed at its specified height and will look only slightly different than it would look when displayed in a non-interlaced View (this is handled by the system automatically). See “Interlaced Mode vs. Non-interlaced Mode” below for more information.

HAM tells the system to use “hold-and-modify” mode, a special mode that lets you display up to 4,096 colors on screen at the same time. It is described in the “Advanced Topics” section.

SPRITES tells the system that you are using sprites in this display (either VSprites or Simple Sprites). The system will load color registers for the sprites. Note that since the mouse pointer is a sprite, omitting this mode will prevent the mouse pointer from being displayed when this ViewPort is frontmost.

See the “Graphics Sprites, Bobs and Animation” chapter for more information about sprites.

EXTRA_HALFBRITE tells the system to use the Extra-Half-Brite mode, a special mode that allows you to display up to 64 colors on screen at the same time. It is described in the “Advanced Topics” section.

If you peruse the <graphics/view.h> include file you will see another flag, EXTENDED_MODE. Never set this flag yourself; it is used by the system to control more advanced mode features.

Be sure to read the section on “Monitors, Modes and the Display Database” for additional information about the ViewPort mode.

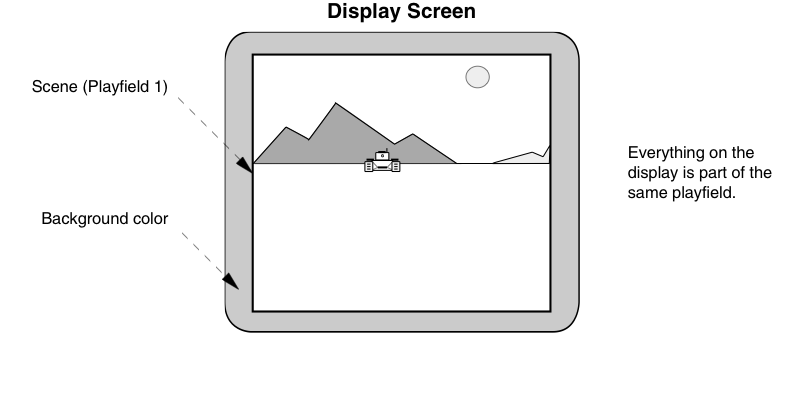

Single-playfield Mode vs. Dual-playfield Mode

When you specify single-playfield mode you are asking that the system treat all bitplanes as part of the definition of a single playfield image. Each of the bitplanes defined as part of this ViewPort contributes data bits that determine the color of the pixels in a single playfield.

Figure 27-12: A Single-playfield Display

If you use dual-playfield mode, you can define two independent, separately controllable playfield areas as shown below.

Figure 27-13: A Dual-playfield Display

In the previous figure, PFBA was included in the display mode. If PFBA had not been included, the relative priorities would have been reversed; playfield 2 would have appeared to be behind playfield 1.

Low-resolution Mode vs. High-resolution Mode

In LORES mode, horizontal lines of 320 pixels fill most of the ordinary viewing area. The system software lets you define a screen segment width up to 362 pixels in this mode, or you can define a screen segment as narrow as you desire (minimum of 16 pixels). In HIRES mode, 640 pixels fill a horizontal line. In this mode you can specify any width from 16 to 724 pixels. In SUPERHIRES mode, 1,280 pixels fill a horizontal line. In this mode you can specify any width from 16 to 1,448 pixels. The fact that many monitor manufacturers set their monitors to overscan the video display normally limits you to showing only 16 to 320 pixels per line in LORES, 16 to 640 pixels per line in HIRES, or 16 to 1,280 pixels per line in SUPERHIRES. The user can set the monitor’s viewable screen size with the Preferences Overscan editor.

Figure 27-14: How HIRES and SUPERHIRES Affect the Width of Pixels

Interlaced Mode vs. Non-interlaced Mode

In interlaced mode, there are twice as many lines available as in non-interlaced mode, providing better vertical resolution in the same display area.

Figure 27-15: How LACE Affects Vertical Resolution

If the View structure does not specify LACE, and the ViewPort specifies LACE, only the top half of the ViewPort data will be displayed.

If the View structure specifies LACE and the ViewPort is non-interlaced, the same ViewPort data will be repeated in both fields. The height of the ViewPort display is the height specified in the ViewPort structure.

If both the View and the ViewPort are interlaced, the ViewPort will be built with double the normal vertical resolution. That means it will need twice as much data space in memory as a non-interlaced picture to fill the display.

ViewPort Display Memory

The picture you create in memory can be larger than the screen image that can be displayed within your ViewPort. This big picture (called a raster and represented by the BitMap structure) can have a maximum size dependent upon the version of the Agnus chip in the Amiga. The ECS Agnus can handle rasters up to 16,384x16,384 pixels. Older Agnus chips are limited to rasters up to 1,024x1,024 pixels. The section on “Determining Chip Versions” earlier in this chapter explains how to find out which Agnus is installed.

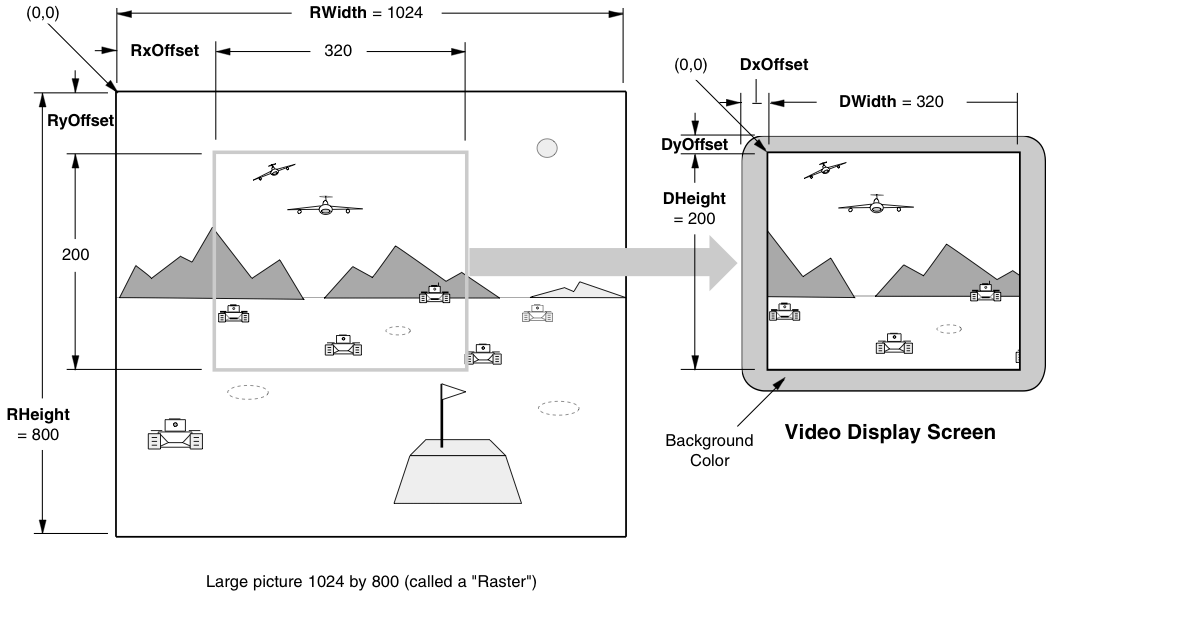

The example in the following figure introduces terms that tell the system how to find the display data and how to display it in the ViewPort. These terms are RHeight, RWidth, RyOffset, RxOffset, DHeight, DWidth, DyOffset and DxOffset.

Figure 27-16: ViewPort Data Area Parameters

The terms RHeight and RWidth do not appear in actual system data structures. They refer to the dimensions of the raster and are used here to relate the size of the raster to the size of the display area.

RHeight is the number of rows in the raster and RWidth is the number of bytes per row times 8. The raster shown in the figure is too big to fit entirely in the display area, so you tell the system which pixel of the raster should appear in the upper left corner of the display segment specified by your ViewPort. The variables that control that placement are RyOffset and RxOffset.

To compute RyOffset and RxOffset, you need RHeight, RWidth, DHeight, and DWidth. The DHeight and DWidth variables define the height and width in pixels of the portion of the display that you want to appear in the ViewPort. The example shows a full-screen, low-resolution mode (320-pixel), non-interlaced (200-line) display formed from the larger overall picture.

Normal values for RyOffset and RxOffset are defined by the formulas:

0 < = RyOffset < = (RHeight - DHeight) 0 < = RxOffset < = (RWidth - DWidth)

Once you have defined the size of the raster and the section of that raster that you wish to display, you need only specify where to put this ViewPort on the screen. This is controlled by the ViewPort variables DyOffset and DxOffset. These are offsets relative to the View.DxOffset and DyOffset.

Possible NTSC values for DyOffset range from -23 to +217 (-46 to +434 if the ViewPort is interlaced), PAL values range from -15 to +267 (-30 to +534 for interlaced ViewPorts). Possible values for DxOffset range from -18 to +362 (-36 to +724 if the ViewPort is Hires, -72 to +1,448 if SuperHires), when the View is in its default, initialized position.

The parameters shown in the figure above are distributed in the following data structures:

- View (information about the whole display) includes the variables that you use to position the whole display on the screen. The View structure contains a Modes field used to determine if the whole display is to be interlaced or non-interlaced. It also contains pointers to its list of ViewPorts and pointers to the Copper instructions produced by the system to create the display you have defined.

- ViewPort (information about this segment of the display) includes the values DxOffset and DyOffset that are used to position this portion relative to the overall View. The ViewPort also contains the variables DHeight and DWidth, which define the size of this display segment; a Modes variable; and a pointer to the local ColorMap. The VideoControl() function and its various tags are used to manipulate the ColorMap and ViewPort.Modes. Each ViewPort also contains a pointer to the next ViewPort. You create a linked list of ViewPorts to define the complete display.

- RasInfo (information about the raster) contains the variables RxOffset and RyOffset. It also contains pointers to the BitMap structure and to a companion RasInfo structure if this is a dual playfield.

- BitMap (information about memory usage) tells the system where to find the display and drawing area memory and shows how this memory space is organized, including the display’s depth.

You must allocate enough memory for the display you define. The memory you use for the display may be shared with the area control structures used for drawing. This allows you to draw into the same areas that you are currently displaying on the screen.

As an alternative, you can define two BitMaps. One of them can be the active structure (that being displayed) and the other can be the inactive structure. If you draw into one BitMap while displaying another, the user cannot see the drawing taking place. This is called double-buffering of the display. See “Advanced Topics” below for an explanation of the steps required for double-buffering. Double-buffering takes twice as much memory as single-buffering because two full displays are produced.

To determine the amount of required memory for each ViewPort for single-buffering, you can use the following formula.

#include <graphics/gfx.h> /* Depth, Width, and Height get set to something reasonable. */ UBYTE Depth, Width, Height; /* Calculate resulting VP size. */ bytes_per_ViewPort = Depth * RASSIZE(Width, Height);

RASSIZE() is a system macro attuned to the current design of the system memory allocation for display rasters. See the <graphics/gfx.h> include file for the formula with which RASSIZE() is calculated.

For example, a 32-color ViewPort (depth = 5), 320 pixels wide by 200 lines high currently uses 40,000 bytes. A 16-color ViewPort (depth = 4), 640 pixels wide by 400 lines high currently uses 128,000 bytes.

Forming a Basic Display

Here are the data structures that you need to define to create a basic display:

struct View view; /* These get used in all versions of the OS */ struct ViewPort viewPort; struct BitMap bitMap; struct RasInfo rasInfo; struct ColorMap *cm; struct ViewExtra *vextra; /* Extra View data, new in Release 2 */ struct ViewPortExtra *vpextra; /* Extra ViewPort data, new in Release 2 */ struct MonitorSpec *monspec; /* Monitor data needed in Release 2 */ struct DimensionInfo dimquery; /* Display dimension data needed in Release 2 */

ViewExtra and ViewPortExtra are data structures used to hold extended data about their corresponding parent structure. ViewExtra contains information about the video monitor being used to render the View. ViewPortExtra contains information required for clipping of the ViewPort.

GfxNew() is used to create these extended data structures and GfxAssociate() is used to associate the extended data structure with an appropriate parent structure. Although GfxAssociate() can associate a ViewPortExtra structure with a ViewPort, it is better to use VideoControl() with the VTAG_VIEWPORTEXTRA_SET tag instead. Keep in mind that GfxNew() allocates memory for the resulting data structure which must be returned using GfxFree() before the application exits. The function GfxLookUp() will find the address of an extended data structure from the address of its parent.

Preparing the View Structure

The following code prepares the View structure for further use:

InitView(&view); /* Initialize the View. */ view.Modes |= LACE; /* Only interlaced, 1.3 displays require this */

A ViewExtra structure must also be created with GfxNew() and associated with this View with GfxAssociate() as shown in the example programs RGBBoxes.c and WBClone.c.

/* Form the ModeID from values in <displayinfo.h> */

modeID=DEFAULT_MONITOR_ID | HIRESLACE_KEY;

/* Make the ViewExtra structure */

if( vextra=GfxNew(VIEW_EXTRA_TYPE) )

{

/* Attach the ViewExtra to the View */

GfxAssociate(&view , vextra);

view.Modes |= EXTEND_VSTRUCT;

/* Initialize the MonitorSpec field of the ViewExtra */

if( monspec=OpenMonitor(NULL,modeID) )

vextra->Monitor=monspec;

else

fail("Could not get MonitorSpec\n");

}

else fail("Could not get ViewExtra\n");

Preparing the BitMap Structure

The BitMap structure tells the system where to find the display and drawing memory and how this memory space is organized. The following code section prepares a BitMap structure, including allocation of memory for the bitmap. This is done with two functions, InitBitMap() and AllocRaster(). InitBitMap() takes four arguments–a pointer to a BitMap and the depth, width, and height of the desired bitmap. Once the bitmap is initialized, memory for its bitplanes must be allocated. AllocRaster() takes two arguments–width and height. Here is a code section to initialize a bitmap:

/* Init BitMap for RasInfo. */

InitBitMap(&bitMap, DEPTH, WIDTH, HEIGHT);

/* Set the plane pointers to NULL so the cleanup routine will

know if they were used. */

for(depth=0; depth<DEPTH; depth++)

bitMap.Planes[depth] = NULL;

/* Allocate space for BitMap. */

for(depth=0; depth<DEPTH; depth++)

{

bitMap.Planes[depth] = (PLANEPTR)AllocRaster(WIDTH, HEIGHT);

if (bitMap.Planes[depth] == NULL)

cleanExit(RETURN_WARN);

}

This code allocates enough memory to handle the display area for as many bitplanes as the depth you have defined.

Preparing the RasInfo Structure

The RasInfo structure provides information to the system about the location of the BitMap as well as the positioning of the display area as a window against a larger drawing area.

Use the following steps to prepare the RasInfo structure:

/* Initialize the RasInfos. */

rasInfo.BitMap = &bitMap; /* Attach the corresponding BitMap. */

rasInfo.RxOffset = 0; /* Align upper left corners of display */

rasInfo.RyOffset = 0; /* with upper left corner of drawing area. */

rasInfo.Next = NULL; /* for a single playfield display, there

* is only one RasInfo structure present */

The system may be made to reinterpret the RxOffset and RyOffset values in a ViewPort’s RasInfo structure by calling ScrollVPort() with the address of the ViewPort. Changing one or both offsets and calling ScrollVPort() has the effect of scrolling the ViewPort.

Preparing the ViewPort Structure

To prepare the ViewPort structure for further use, you call InitVPort() and initialize certain fields as follows:

InitVPort(&viewPort); /* Initialize the ViewPort. */ viewPort.RasInfo = &rasInfo; /* The rasInfo must also be initialized */ viewPort.DWidth = WIDTH; viewPort.DHeight = HEIGHT; /* Under 1.3, you should set viewPort.Modes here to select a display mode. */ /* Under Release 2, use VideoControl() with VTAG_NORMAL_DISP_SET to select */ /* a display mode by attaching a DisplayInfo structure to the ViewPort. */

The InitVPort() routine presets certain default values in the ViewPort structure. The defaults include:

- Modes variable set to zero–this means you select a low-resolution display. (To alter this, use VideoControl() with the VTAG_NORMAL_DISP_SET tag as explained below.)

- Next variable set to NULL–no other ViewPort is linked to this one. If you want a display with multiple ViewPorts, you must fill in the link yourself.

If you want to create a View with two or more ViewPorts you must declare and initialize the ViewPorts as above. Then link them together using the ViewPort.Next field with a NULL link for the ViewPort at the end of the chain:

viewPortA.Next = &viewPortB; /* Tell first one the address of the second. */ viewPortB.Next = NULL; /* There are no others after this one. */

Once a ViewPort has been prepared, a ViewPortExtra structure must also be created with GfxNew(), initialized, and associated with the ViewPort via the VideoControl() function. In addition, a DisplayInfo for this mode must be attached to the ViewPort. The fragment below shows how to do this. For complete examples, refer to the program listings of RGBBoxes.c and WBClone.c.

struct TagItem vcTags[] = /* These tags will be passed to the */

{ /* VideoControl() function to set up */

{ VTAG_ATTACH_CM_SET, NULL }, /* the extended ViewPort structures */

{ VTAG_VIEWPORTEXTRA_SET, NULL }, /* required in Release 2. The NULL */

{ VTAG_NORMAL_DISP_SET, NULL }, /* ti_Data field of these tags must */

{ VTAG_END_CM, NULL } /* be filled in before making the */

}; /* call to VideoControl(). */

struct DimensionInfo dimquery; /* Release 2 structure for display size data */

/* Make a ViewPortExtra and get ready to attach it */

if( vpextra = GfxNew(VIEWPORT_EXTRA_TYPE) )

{

vcTags[1].ti_Data = (ULONG) vpextra;

/* Initialize the DisplayClip field of the ViewPortExtra structure */

if( GetDisplayInfoData( NULL , (UBYTE *) &dimquery ,

sizeof(struct dimquery) , DTAG_DIMS, modeID) )

{

vpextra->DisplayClip = dimquery.Nominal;

/* Make a DisplayInfo and get ready to attach it */

if( !(vcTags[2].ti_Data = (ULONG) FindDisplayInfo(modeID)) )

fail("Could not get DisplayInfo\n");

}

else fail("Could not get DimensionInfo\n");

}

else fail("Could not get ViewPortExtra\n");

/* This is for backwards compatibility with, for example, */

/* a 1.3 screen saver utility that looks at the Modes field */

viewPort.Modes = (UWORD) (modeID & 0x0000ffff);

Preparing the ColorMap Structure

When the View is created, Copper instructions are generated to change the current contents of each color register just before the topmost line of a ViewPort so that this ViewPort’s color registers will be used for interpreting its display. To set the color registers you create a ColorMap for the ViewPort with GetColorMap() and call SetRGB4(). Here are the steps used in 1.3 to initialize a ColorMap:

if( view.ColorMap=GetColorMap( 4L ) )

LoadRGB4((&viewPort, colortable, 4);

A ColorMap is attached to the View–usually along with DisplayInfo and ViewExtra–by calling the VideoControl() function.

/* RGB values for the four colors used. */

#define BLACK 0x000

#define RED 0xf00

#define GREEN 0x0f0

#define BLUE 0x00f

/* Define some colors in an array of UWORDS. */

static UWORD colortable[] = { BLACK, RED, GREEN, BLUE };

/* Fill the TagItem Data field with the address of the properly initialized

(including ViewPortExtra) structure to be passed to VideoControl(). */

vc[0].ti_Data = (ULONG)viewPort;

/* Init ColorMap. 2 planes deep, so 4 entries (2 raised to #planes power). */

if(cm = GetColorMap( 4L ) )

{

/* For applications that must be compatible with 1.3, replace the next 2 */

/* lines with: viewPort.ColorMap=cm; */

if( VideoControl( cm , vcTags ) )

fail("Could not attach extended structures\n");

/* Change colors to those in colortable. */

LoadRGB4(&viewPort, colortable, 4);

}

| The 4 Is For Bits, Not Entries. |

|---|

| The 4 in the name LoadRGB4() refers to the fact that each of the red, green, and blue values in a color table entry consists of four bits. It has nothing to do with the fact that this particular color table contains four entries. The call GetRGB4() returns the RGB value of a single entry of a ColorMap. SetRGB4CM() allows individual control of the entries in the ColorMap before or after linking it into the ViewPort. |

The LoadRGB4() call above could be replaced with the following:

register USHORT entry;

/* Operate on the same four ColorMap entries as above. */

for (entry = 0; entry < 4; entry++)

{

/* Call SetRGB4CM() with the address of the ColorMap, the entry to be

changed, and the Red, Green, and Blue values to be stored there.

*/

SetRGB4CM(viewPort.ColorMap, entry,

/* Extract the three color values from the one colortable entry. */

((colortable[entry] & 0x0f00) >> 8),

((colortable[entry] & 0x00f0) >> 4),

(colortable[entry] & 0x000f));

}

Notice above how the four bits for each color are masked out and shifted right to get values from 0 to 15.

| WARNING! |

|---|

| It is important to use only the standard system ColorMap-related calls to access the ColorMap entries. These calls will remain compatible with recent and future enhancements to the ColorMap structure. |

You might need to specify more colors in the color map than you think. If you use a dual playfield display (covered later in this chapter) with a depth of 1 for each of the two playfields, this means a total of four colors (two for each playfield). However, because playfield 2 uses color registers starting from number 8 on up when in dual-playfield mode, the color map must be initialized to contain at least 10 entries.

That is, it must contain entries for colors 0 and 1 (for playfield 1) and color numbers 8 and 9 (for playfield 2). Space for sprite colors must be allocated as well. For Amiga system software version 1.3 and earlier, when in doubt, allocate a ColorMap with 32 entries, just in case.

Creating the Display Instructions

Now that you have initialized the system data structures, you can request that the system prepare a set of display instructions for the Copper using these structures as input data.

During the one or more blank vertical lines that precede each ViewPort, the Copper is busy changing the characteristics of the display hardware to match the characteristics you expect for this ViewPort.

This may include a change in display resolution, a change in the colors to be used, or other user-defined modifications to system registers.

Here is the code that creates the display instructions:

/* Construct preliminary Copper instruction list. */ MakeVPort( &view, &viewPort );

In this line of code, &view is the address of the View structure and &viewPort is the address of the first ViewPort structure. Using these structures, the system has enough information to build the instruction stream that defines your display.

MakeVPort() creates a special set of instructions that controls the appearance of the display.

If you are using animation, the graphics animation routines create a special set of instructions to control the hardware sprites and the system color registers.

In addition, the advanced user can create special instructions (called user Copper instructions) to change system operations based on the position of the video beam on the screen.

All of these special instructions must be merged together before the system can use them to produce the display you have designed. This is done by the system routine MrgCop() (which stands for “Merge Coprocessor Instructions”). Here is a typical call:

/* Merge preliminary lists into a real Copper list in the view structure. */ MrgCop( &view );

Loading and Displaying the View

To display the View, you need to load it using LoadView() and turn on the direct memory access (DMA). A typical call is shown below.

LoadView(&view);

The &view argument is the address of the View structure defined in the example above.

There are two macros, defined in <graphics/gfxmacros.h>, that control display DMA: ON_DISPLAY and OFF_DISPLAY. They simply turn the display DMA control bit in the DMA control register on or off.

If you are drawing to the display area and do not want the user to see intermediate steps in the drawing, you can turn off the display. Because OFF_DISPLAY shuts down the display DMA and possibly speeds up other system operations, it can be used to provide additional memory cycles to the blitter or the 68000. The distribution of system DMA, however, allows four-channel sound, disk read/write, and a sixteen-color, low-resolution display (or four-color, high-resolution display) to operate at the same time with no slowdown (7.1 MHz effective rate) in the operation of the 68000. Using OFF_DISPLAY in a multitasking environment may, however, be an unfriendly thing to do to the other running processes. Use OFF_DISPLAY with discretion.

A Custom ViewPort Example

The following example creates a View consisting of one ViewPort set to an NTSC, high-resolution, interlaced display mode of nominal dimensions. This example shows both the old 1.3 way of setting up the ViewPort and the new method used in Release 2.

;/* RGBBoxes.c simple ViewPort example -- works with 1.3 and Release 2

LC -b1 -cfistq -v -y -j73 RGBBoxes.c

Blink FROM LIB:c.o,RGBBoxes.o TO RGBBoxes LIBRARY LIB:LC.lib,LIB:Amiga.lib

quit

*/

#include <exec/types.h>

#include <graphics/gfx.h>

#include <graphics/gfxbase.h>

#include <graphics/gfxmacros.h>

#include <graphics/copper.h>

#include <graphics/view.h>

#include <graphics/displayinfo.h>

#include <graphics/gfxnodes.h>

#include <graphics/videocontrol.h>

#include <libraries/dos.h>

#include <utility/tagitem.h>

#include <clib/graphics_protos.h>

#include <clib/exec_protos.h>

#include <clib/dos_protos.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define DEPTH 2 /* The number of bitplanes. */

#define WIDTH 640 /* Nominal width and height */

#define HEIGHT 400 /* used in 1.3. */

#ifdef LATTICE

int CXBRK(void) { return(0); } /* Disable Lattice CTRL/C handling */

int chkabort(void) { return(0); } /* really */

#endif

VOID drawFilledBox(WORD , WORD ); /* Function prototypes */

VOID cleanup(int );

VOID fail(STRPTR);

struct GfxBase *GfxBase = NULL;

/* Construct a simple display. These are global to make freeing easier. */

struct View view, *oldview=NULL; /* Pointer to old View we can restore it.*/

struct ViewPort viewPort = { 0 };

struct BitMap bitMap = { 0 };

struct ColorMap *cm=NULL;

struct ViewExtra *vextra=NULL; /* Extended structures used in Release 2 */

struct MonitorSpec *monspec=NULL;

struct ViewPortExtra *vpextra=NULL;

struct DimensionInfo dimquery = { 0 };

UBYTE *displaymem = NULL; /* Pointer for writing to BitMap memory. */

#define BLACK 0x000 /* RGB values for the four colors used. */

#define RED 0xf00

#define GREEN 0x0f0

#define BLUE 0x00f

/*

* main(): create a custom display; works under either 1.3 or Release 2

*/

VOID main(VOID)

{

WORD depth, box;

struct RasInfo rasInfo;

ULONG modeID;

struct TagItem vcTags[] =

{

{VTAG_ATTACH_CM_SET, NULL },

{VTAG_VIEWPORTEXTRA_SET, NULL },

{VTAG_NORMAL_DISP_SET, NULL },

{VTAG_END_CM, NULL }

};

/* Offsets in BitMap where boxes will be drawn. */

static SHORT boxoffsets[] = { 802, 2010, 3218 };

static UWORD colortable[] = { BLACK, RED, GREEN, BLUE };

/* Open the graphics library */

GfxBase = (struct GfxBase *)OpenLibrary("graphics.library", 33L);

if(GfxBase == NULL)

fail("Could not open graphics library\n");

/* Example steals screen from Intuition if Intuition is around. */

oldview = GfxBase->ActiView; /* Save current View to restore later. */

InitView(&view); /* Initialize the View and set View.Modes. */

view.Modes |= LACE; /* This is the old 1.3 way (only LACE counts). */

if(GfxBase->LibNode.lib_Version >= 36)

{

/* Form the ModeID from values in <displayinfo.h> */

modeID=DEFAULT_MONITOR_ID | HIRESLACE_KEY;

/* Make the ViewExtra structure */

if( vextra=GfxNew(VIEW_EXTRA_TYPE) )

{

/* Attach the ViewExtra to the View */

GfxAssociate(&view , vextra);

view.Modes |= EXTEND_VSTRUCT;

/* Create and attach a MonitorSpec to the ViewExtra */

if( monspec=OpenMonitor(NULL,modeID) )

vextra->Monitor=monspec;

else

fail("Could not get MonitorSpec\n");

}

else fail("Could not get ViewExtra\n");

}

/* Initialize the BitMap for RasInfo. */

InitBitMap(&bitMap, DEPTH, WIDTH, HEIGHT);

/* Set the plane pointers to NULL so the cleanup routine */

/* will know if they were used. */

for(depth=0; depth<DEPTH; depth++)

bitMap.Planes[depth] = NULL;

/* Allocate space for BitMap. */

for (depth=0; depth<DEPTH; depth++)

{

bitMap.Planes[depth] = (PLANEPTR)AllocRaster(WIDTH, HEIGHT);

if (bitMap.Planes[depth] == NULL)

fail("Could not get BitPlanes\n");

}

rasInfo.BitMap = &bitMap; /* Initialize the RasInfo. */

rasInfo.RxOffset = 0;

rasInfo.RyOffset = 0;

rasInfo.Next = NULL;

InitVPort(&viewPort); /* Initialize the ViewPort. */

view.ViewPort = &viewPort; /* Link the ViewPort into the View. */

viewPort.RasInfo = &rasInfo;

viewPort.DWidth = WIDTH;

viewPort.DHeight = HEIGHT;

/* Set the display mode the old-fashioned way */

viewPort.Modes=HIRES | LACE;

if(GfxBase->LibNode.lib_Version >= 36)

{

/* Make a ViewPortExtra and get ready to attach it */

if( vpextra = GfxNew(VIEWPORT_EXTRA_TYPE) )

{

vcTags[1].ti_Data = (ULONG) vpextra;

/* Initialize the DisplayClip field of the ViewPortExtra */

if( GetDisplayInfoData( NULL , (UBYTE *) &dimquery ,

sizeof(dimquery) , DTAG_DIMS, modeID) )

{

vpextra->DisplayClip = dimquery.Nominal;

/* Make a DisplayInfo and get ready to attach it */

if( !(vcTags[2].ti_Data = (ULONG) FindDisplayInfo(modeID)) )

fail("Could not get DisplayInfo\n");

}

else fail("Could not get DimensionInfo \n");

}

else fail("Could not get ViewPortExtra\n");

/* This is for backwards compatibility with, for example, */

/* a 1.3 screen saver utility that looks at the Modes field */

viewPort.Modes = (UWORD) (modeID & 0x0000ffff);

}

/* Initialize the ColorMap. */

/* 2 planes deep, so 4 entries (2 raised to the #_planes power). */

cm = GetColorMap(4L);

if(cm == NULL)

fail("Could not get ColorMap\n");

if(GfxBase->LibNode.lib_Version >= 36)

{

/* Get ready to attach the ColorMap, Release 2-style */

vcTags[0].ti_Data = (ULONG) &viewPort;

/* Attach the color map and Release 2 extended structures */

if( VideoControl(cm,vcTags) )

fail("Could not attach extended structures\n");

}

else

/* Attach the ColorMap, old 1.3-style */

viewPort.ColorMap = cm;

LoadRGB4(&viewPort, colortable, 4); /* Change colors to those in colortable. */

MakeVPort( &view, &viewPort ); /* Construct preliminary Copper instruction list. */

/* Merge preliminary lists into a real Copper list in the View structure. */

MrgCop( &view );

/* Clear the ViewPort */

for(depth=0; depth<DEPTH; depth++)

{

displaymem = (UBYTE *)bitMap.Planes[depth];

BltClear(displaymem, (bitMap.BytesPerRow * bitMap.Rows), 1L);

}

LoadView(&view);

/* Now fill some boxes so that user can see something. */

/* Always draw into both planes to assure true colors. */

for (box=1; box<=3; box++) /* Three boxes; red, green and blue. */

{

for (depth=0; depth<DEPTH; depth++) /* Two planes. */

{

displaymem = bitMap.Planes[depth] + boxoffsets[box-1];

drawFilledBox(box, depth);

}

}

Delay(10L * TICKS_PER_SECOND); /* Pause for 10 seconds. */

LoadView(oldview); /* Put back the old View. */

WaitTOF(); /* Wait until the the View is being */

/* rendered to free memory. */

FreeCprList(view.LOFCprList); /* Deallocate the hardware Copper list */

if(view.SHFCprList) /* created by MrgCop(). Since this */

FreeCprList(view.SHFCprList);/* is interlace, also check for a */

/* short frame copper list to free. */

FreeVPortCopLists(&viewPort); /* Free all intermediate Copper lists */

/* from created by MakeVPort(). */

cleanup(RETURN_OK); /* Success. */

}

/*

* fail(): print the error string and call cleanup() to exit

*/

void fail(STRPTR errorstring)

{

printf(errorstring);

cleanup(RETURN_FAIL);

}

/*

* cleanup(): free everything that was allocated.

*/

VOID cleanup(int returncode)

{

WORD depth;

/* Free the color map created by GetColorMap(). */

if(cm) FreeColorMap(cm);

/* Free the ViewPortExtra created by GfxNew() */

if(vpextra) GfxFree(vpextra);

/* Free the BitPlanes drawing area. */

for(depth=0; depth<DEPTH; depth++)

{

if (bitMap.Planes[depth])

FreeRaster(bitMap.Planes[depth], WIDTH, HEIGHT);

}

/* Free the MonitorSpec created with OpenMonitor() */

if(monspec) CloseMonitor( monspec );

/* Free the ViewExtra created with GfxNew() */

if(vextra) GfxFree(vextra);

/* Close the graphics library */

CloseLibrary((struct Library *)GfxBase);

exit(returncode);

}

/*

* drawFilledBox(): create a WIDTH/2 by HEIGHT/2 box of color

* "fillcolor" into the given plane.

*/

VOID drawFilledBox(WORD fillcolor, WORD plane)

{

UBYTE value;

WORD boxHeight, boxWidth, width;

/* Divide (WIDTH/2) by eight because each UBYTE that */

/* is written stuffs eight bits into the BitMap. */

boxWidth = (WIDTH/2)/8;

boxHeight = HEIGHT/2;

value = ((fillcolor & (1 << plane)) != 0) ? 0xff : 0x00;

for( ; boxHeight; boxHeight--)

{

for(width=0 ; width < boxWidth; width++)

*displaymem++ = value;

displaymem += (bitMap.BytesPerRow - boxWidth);

}

}

Exiting Gracefully

The preceding sample program provides a way of exiting gracefully with the cleanup() subroutine. This function returns to the memory manager all dynamically-allocated memory chunks. Notice the calls to FreeRaster() and FreeColorMap(). These calls correspond directly to the allocation calls AllocRaster() and GetColorMap() located in the body of the program. Now look at the calls within cleanup() to FreeVPortCopLists() and FreeCprList(). When you call MakeVPort(), the graphics system dynamically allocates some space to hold intermediate instructions from which a final Copper instruction list is created. When you call MrgCop(), these intermediate Copper lists are merged together into the final Copper list, which is then given to the hardware for interpretation. It is this list that provides the stable display on the screen, split into separate ViewPorts with their own colors and resolutions and so on.

When your program completes, you must see that it returns all of the memory resources that it used so that those memory areas are again available to the system for reassignment to other tasks. Therefore, if you use the routines MakeVPort() or MrgCop(), you must also arrange to use FreeCprList() (pointing to each of those lists in the View structure) and FreeVPortCopLists() (pointing to the ViewPort that is about to be deallocated). If your View is interlaced, you will also have to call FreeCprList(&view.SHFCprList) because an interlaced view has a separate Copper list for each of the two fields displayed. Do not confuse FreeVPortCopLists() with FreeCprList(). The former works on intermediate Copper lists for a specific ViewPort, the latter directly on a hardware Copper list from the View.

As a final caveat, notice that when you do free everything, the memory manager or other programs may immediately change the contents of the freed memory. Therefore, if the Copper is still executing an instruction stream (as a result of a previous LoadView()) when you free that memory, the display will malfunction. Once another View has been installed via LoadView(), do a WaitTOF() for the new View to begin displaying, and then you can begin freeing up your resources. WaitTOF() waits for the vertical blanking period to begin and all vertical blank interrupts to complete before returning to the caller. The routine WaitBOVP() (for “WaitBottomOfViewPort”) busy waits until the vertical beam reaches the bottom of the specified ViewPort before returning to the caller. This means no other tasks run until this function returns.

Monitors, Modes and the Display Database

The graphics library supports a variety of new video monitors, and new programmable video modes not available in older versions of the operating system. Inquiries about the availability of these modes, their dimensions and currently accessible options can be made through a database indexed by the same key information used to open Intuition screens. This design provides a good degree of compatibility with existing software, between differently equipped hardware platforms and for both static and dynamic data storage.

The software may be running on A1000 computers which will not have ECS, on A500 computers which may not have the latest ECS upgrade, and on A2000 computers which generally have the latest ECS but may not have a multi-sync monitor currently attached. This means that there are compatibility issues to consider–what should happen when a required ECS or monitor resource is not available for the desired mode.

Here are the compatibility criteria, in a simplified fashion:

- Requires Release 2, and ECS Chips only

- SuperHires mode (35nS pixel resolutions). This allows for very high horizontal resolutions with the new ECS chip set and a standard NTSC or PAL monitor. (SuperHires has twice as much horizontal resolution as the old Hires mode.)

- Requires Release 2, ECS Chips, and appropriate monitor

- Productivity mode. This allows for flicker-free 640 x 480 color displays with the addition of a multi-sync or bi-sync 31 Khz monitor. (Productivity mode conforms, in a general way, to the VGA Mode 3 Standard 8514/A.)

- Requires Release 2 (or the V35 of graphics.library under 1.3) and appropriate monitor only

- A2024 Scan Conversion. This allows for a very high resolution grayscale display, typically 1,008<math>\times</math>800, suitable for desktop publishing or similar applications. A special video monitor is required (the monitor also supports the normal Amiga modes in greyscale).

- Requires Release 2 but not ECS Chips or appropriate monitor

- Display database inquiries. This allows for programmers to determine if the required resources are currently available for the requested mode.

In addition, there are fallback modes (which do not require Release 2) which resort to some reasonable display when a required resource is not available.

New Monitors

Currently, there are five possible monitor settings in the display database (more may be added in future releases):

- default.monitor

- Since the default system monitor must be capable of displaying an image no matter what chips are installed or what software revision is in ROM, the graphics.library default.monitor is defined as a 15 kHz monitor which can display NTSC in the U.S. or PAL in Europe.

- ntsc.monitor

- Since the ECS chip set allows for dynamic choice of standard scan rates, NTSC applications running on European machines may choose to be displayed on the ntsc.monitor to preserve the aspect ratio.

- pal.monitor

- Since the ECS chip set allows for dynamic choice of standard scan rates, PAL applications running on American machines may choose to be displayed on the pal.monitor to preserve the aspect ratio.

- multisync.monitor

- Programmably variable scan rates from 15 kHz through 31 kHz or more. Responds to signal timings to decide what scan rate to display. Required for Productivity (640x480x2 non-interlaced) display.

- A2024.monitor

- Scan converter monitor which provides 1,008x800x2 (U.S.) or 1,008x1,024x2 (European) high-resolution, greyscale display. Does not require ECS. Does require Release 2 (or 1.3 V35) graphics library.

New Modes

In V1.3 and earlier versions of the OS, the mode for a display was determined by a 16 bit-value specified either in the ViewPort.Modes field (for displays set up with the graphics library) or in the NewScreen.ViewModes field (for displays set up with Intuition). Prior to Release 2, it was sufficient to indicate the mode of a display by setting bits in the ViewPort.Modes field. Furthermore, programs routinely made interpretations about a given display mode based on bit-by-bit testing of this 16-bit value.

The approach taken in Release 2 and later is to utilize a 32-bit display mode specifier called a ModeID. The upper half of this specifier is called the monitor part and the lower half is informally called the mode part. There is a correspondence between the monitor part and the monitor’s operating modes (referred to as virtual monitors or MonitorSpecs after a system data structure).

For example, the A2024 monitor, PAL and NTSC are all different virtual monitors–the actual, physical monitor may be able to support more than one of these virtual types. Another new concept in Release 2 is the default monitor. The default monitor, represented by a zero value for the ModeID monitor part, may be either PAL or NTSC depending on a jumper on the motherboard.

Compatibility considerations-especially for IFF files and their CAMG chunk–have dictated very careful choices for the bit values which make up the mode part of the 32-bit ModeIDs. For example, the ModeIDs corresponding to the older, 1.3 display modes have been constructed out of a zero in the monitor part and the old 16-bit ViewPort.Modes bits in the lower part (after several extraneous bits such as SPRITES and VP_HIDE are cleared).

There are other such coincidences, but steps for compatibility with old programs notwithstanding, there is a new rule:

Programmers shall never interpret ModeIDs on a bit-by-bit basis.

For example, if the HIRES bit is set it does not mean the display is 640 pixels wide because there can also be a doubling of the beam scan rate. Programs should not attempt to interpret modes directly from the ViewPort.Modes field. The graphics library provides a suitable substitute for this information through its new display database facility (explained below).

Likewise, the Mode of a ViewPort is no longer set directly. Instead it is set indirectly by associating the ViewPort with an abstract, 32-bit ModeID via the VideoControl() function.

These 32-bit ModeIDs have been carefully designed so that their lower 16 bits, when passed to graphics in the ViewPort.Modes field, provide some degree of compatibility between different systems. Older V1.3 programs will continue to work within the new scheme. (They will, however, not gain the benefits of the new modes and monitors available.)

Refer to the example program, WBClone.c, at the end of this section for examples on opening ViewPorts using a ModeID specification.

Mode Specification, Screen Interface

Opening an Intuition screen in one of the new modes requires the specification of 32 bits of mode data. The NewScreen.ViewModes field is a UWORD (16 bits). Therefore, the function OpenScreenTags() must be used along with a SA_DisplayID tag which specifies the 32-bit ModeID. See the “Intuition Screens” chapter for more on this.

The new display modes also introduce some complexity for applications that want to support “mode-sensitive” processing. If a program wishes to open a screen in the highest resolution that a user has available there are many more cases to handle. Therefore, it will become increasingly important to algorithmically layout a screen for correct, functional and aesthetic operation. All the information needed to be mode-flexible is available through the display database functions (explained below).

Mode Specification, ViewPort Interface

When working directly with graphics, the interface is based on View and ViewPort structures, rather than on Intuition’s Screen structure. As previously mentioned, new information must be associated with the ViewPort to specify the new modes, and also with the View to specify what virtual monitor the whole View will be displayed on. There is also a lot of information to associate with a ViewPort regarding enhanced genlock capabilities.

This association of this new data with the View is made through a display database system which has been added to graphics library. All correctly written programs that allocate a ColorMap structure for a ViewPort use the GetColorMap() function to do it. Hence, the ColorMap structure is used as the general purpose black box extension of the ViewPort data.

To set or obtain the data in the extended structures, use a function named VideoControl() takes a ColorMap as an argument. This allows the setting and getting of the extended display data. This mechanism is used to associate a DisplayInfo handle (not a ModeID) with a ViewPort. A DisplayInfo handle is an abstract link to the display database area associated with a particular ModeID. This handle is passed to the graphics database functions when getting or setting information about the mode.

Using VideoControl(), a program can enable, disable, or obtain the state of a ViewPort’s ColorMap, mode, genlock and other features. The function uses a tag based interface and returns NULL if no error occurred.

error = BOOL VideoControl( struct ColorMap *cm, struct TagItem *tag );

The first argument is a pointer to a ColorMap structure as returned by the GetColorMap() function. The second argument is a pointer to an array of video control tag items, used to indicate whether information is being given or requested as well as to pass (or receive the information). The tags you can use with VideoControl() include the following:

VTAG_ATTACH_CM_GET (or _SET) is used to obtain the ColorMap structure from the indicated ViewPort or attach a given ColorMap to it.

VTAG_VIEWPORTEXTRA_GET (or _SET) is used to obtain the ViewPortExtra structure from the indicated ColorMap structure or attach a given ViewPortExtra to it. A ViewPortExtra structure is an extension of the ViewPort structure and should be allocated and freed with GfxNew() and GfxFree() and associated with the ViewPort with VideoControl().

VTAG_NORMAL_DISP_GET (or _SET) is used to obtain or set the DisplayInfo structure for the standard or “normal” mode.

See <graphics/videocontrol.h> for a list of all the available tags. See the section on genlocking for information on using VideoControl() to interact with the Amiga’s genlock capabilities. Note that the graphics library will modify the tag list passed to VideoControl().

Coexisting Modes

Each display mode specifies (among other things) a pixel resolution and a monitor scan rate. Though the Amiga has the unique ability to change pixel resolutions on the fly, it is not possible to change the speed of a monitor beam in mid-frame.

Therefore, if you set up a display of two or more ViewPorts in different display modes requiring different scan rates, at least one of the ViewPorts will be displayed with the wrong scan rate.

Such ViewPorts can be coerced into a different mode designed for the scan rate currently in effect. You can do this in a couple of ways, introducing or removing interlace to adjust the vertical dimension, and changing to faster or slower pixels (higher or lower resolution) for the horizontal dimension.

The disadvantage of introducing interlace is flicker. The disadvantage of increasing resolution is the lessening of the video bus bandwidth and possibly a reduction in the number of colors or palette resolution.

Under Intuition, the frontmost screen determines which of the conflicting modes will take precedence. With the graphics library, the Modes field of the View and its frontmost ViewPort or, in Release 2, the MonitorSpec of the ViewExtra determine the scan rate. For some monitors (such as the A2024), simultaneous display is excluded. This is a requirement only because the A2024 modes require very special and intricate display Copper list management.

ModeID Identifiers

The following definitions appear in the include file <graphics/displayinfo.h>. These values form the 32-bit ModeID which consists of a _MONITOR_ID in the upper word, and a _MODE_KEY in the lower word. Never interpret these bits directly. Instead use them with the display database to obtain the information you need about the display mode.

/* normal identifiers */ #define MONITOR_ID_MASK 0xFFFF1000 #define DEFAULT_MONITOR_ID 0x00000000 #define NTSC_MONITOR_ID 0x00011000 #define PAL_MONITOR_ID 0x00021000 /* the following 20 composite keys are for Modes on the default Monitor */ /* NTSC & PAL "flavors" of these particular keys may be made by OR'ing */ /* the NTSC or PAL MONITOR_ID with the desired MODE_KEY... */ #define LORES_KEY 0x00000000 #define HIRES_KEY 0x00008000 #define SUPER_KEY 0x00008020 #define HAM_KEY 0x00000800 #define LORESLACE_KEY 0x00000004 #define HIRESLACE_KEY 0x00008004 #define SUPERLACE_KEY 0x00008024 #define HAMLACE_KEY 0x00000804 #define LORESDPF_KEY 0x00000400 #define HIRESDPF_KEY 0x00008400 #define SUPERDPF_KEY 0x00008420 #define LORESLACEDPF_KEY 0x00000404 #define HIRESLACEDPF_KEY 0x00008404 #define SUPERLACEDPF_KEY 0x00008424 #define LORESDPF2_KEY 0x00000440 #define HIRESDPF2_KEY 0x00008440 #define SUPERDPF2_KEY 0x00008460 #define LORESLACEDPF2_KEY 0x00000444 #define HIRESLACEDPF2_KEY 0x00008444 #define SUPERLACEDPF2_KEY 0x00008464 #define EXTRAHALFBRITE_KEY 0x00000080 #define EXTRAHALFBRITELACE_KEY 0x00000084 /* vga identifiers */ #define VGA_MONITOR_ID 0x00031000 #define VGAEXTRALORES_KEY 0x00031004 #define VGALORES_KEY 0x00039004 #define VGAPRODUCT_KEY 0x00039024 #define VGAHAM_KEY 0x00031804 #define VGAEXTRALORESLACE_KEY 0x00031005 #define VGALORESLACE_KEY 0x00039005 #define VGAPRODUCTLACE_KEY 0x00039025 #define VGAHAMLACE_KEY 0x00031805 #define VGAEXTRALORESDPF_KEY 0x00031404 #define VGALORESDPF_KEY 0x00039404 #define VGAPRODUCTDPF_KEY 0x00039424 #define VGAEXTRALORESLACEDPF_KEY 0x00031405 #define VGALORESLACEDPF_KEY 0x00039405 #define VGAPRODUCTLACEDPF_KEY 0x00039425 #define VGAEXTRALORESDPF2_KEY 0x00031444 #define VGALORESDPF2_KEY 0x00039444 #define VGAPRODUCTDPF2_KEY 0x00039464 #define VGAEXTRALORESLACEDPF2_KEY 0x00031445 #define VGALORESLACEDPF2_KEY 0x00039445 #define VGAPRODUCTLACEDPF2_KEY 0x00039465 #define VGAEXTRAHALFBRITE_KEY 0x00031084 #define VGAEXTRAHALFBRITELACE_KEY 0x00031085 /* a2024 identifiers */ #define A2024_MONITOR_ID 0x00041000 #define A2024TENHERTZ_KEY 0x00041000 #define A2024FIFTEENHERTZ_KEY 0x00049000 /* prototype identifiers */ #define PROTO_MONITOR_ID 0x00051000

The Display Database and the DisplayInfo Record

For each ModeID, the graphics library has a body of data that enables the set up of the display hardware and provides applications with information about the properties of the display mode.

The display information in the database is accessed by searching it for a record with a given ModeID. For performance reasons, a look-up function named FindDisplayInfo() is provided which, given a ModeID, will return a handle to the internal data record about the attributes of the display.

This handle is then used for queries to the display database and specification of display mode to the low-level graphics routines. It is never used as a pointer. The private data structure associated with a given ModeID is called a DisplayInfo. From the <graphics/displayinfo.h> include file:

/* the "public" handle to a DisplayInfo */ typedef APTR DisplayInfoHandle;

In order to obtain database information about an existing ViewPort, you must first gain reference to its 32-bit ModeID. A graphics function GetVPModeID() simplifies this operation:

modeID = ULONG GetVPModeID(struct ViewPort *vp )

The vp argument is pointer to a ViewPort structure. This function returns the normal display ModeID, if one is currently associated with this ViewPort. If no ModeID exists this function returns INVALID_ID.

Each new valid 32-bit ModeID is associated with data initialized by the graphics library at powerup. This data is accessed by obtaining a handle to it with the graphics function FindDisplayInfo().

handle = DisplayInfoHandle FindDisplayInfo(ULONG modeID);

Given a 32-bit ModeID key (modeID in the prototype above) FindDisplayInfo() returns a handle to a valid DisplayInfoRecord found in the graphics database, or NULL. Using this handle, you can obtain information about this video mode, including its default dimensions, properties and whether it is currently available for use.

For instance, you can use a DisplayInfoHandle with the GetDisplayInfoData() function to look up the properties of a mode (see below). Or use the DisplayInfoHandle with VideoControl() and the VTAG_NORMAL_DISP_SET tag to set up a custom ViewPort.

Accessing the DisplayInfo

Basic information about a display can be obtained by calling the Release 2 graphics function GetDisplayInfoData(). You also call this function during the set up of a ViewPort.

result = ULONG GetDisplayInfoData( DisplayInfoHandle handle, UBYTE *buf,

ULONG size, ULONG tagID, ULONG modeID )

Set the handle argument to the DisplayInfoHandle returned by a previous call to FindDisplayInfo(). This function will also accept a 32-bit ModeID directly as an argument. The handle argument should be set to NULL in that case.

The buf argument points to a destination buffer you have set up to hold the information about the properties of the display. The size argument gives the size of the buffer which depends on the type of inquiry you make.

The tagID argument specifies the type information you want to know about and may be set as follows:

- DTAG_DISP

- Returns display properties and availability information (the buffer should be set to the size of a DisplayInfo structure).

- DTAG_DIMS

- Returns default dimensions and overscan information (the buffer should be set to the size of a DimensionInfo structure).

- DTAG_MNTR

- Returns monitor type, view position, scan rate, and compatibility (the buffer should be set to the size of a MonitorInfo structure).

- DTAG_NAME

- Returns the user friendly name for this mode (the buffer should be set to the size of a NameInfo structure).

If the call succeeds, result is positive and reports the number of bytes actually transferred to the buffer. If the call fails (no information for the ModeID was available), result is zero.

Mode Availability

Even if the video monitor (NTSC, PAL, VGA, A2024) or ECS chips required to support a given mode are not available, there will be a DisplayInfo for all of the display modes. (This will not be the case for disk-based modes such as Euro36, Euro72, etc.)

Thus, the graphics library provides the ModeNotAvailable() function to determine whether a given mode is available, and if not, why not. Data corruption might cause the look-up function, GetVPModeID(), to fail even when it should not, so the careful programmer will always test the look-up function’s return value.

error = ULONG ModeNotAvailable( ULONG modeID )

The modeID argument is again a 32-bit ModeID as shown in <graphics/displayinfo.h>. This function returns an error code, indicating why this modeID is not available, or NULL if there is no known reason why this mode should not be there. The ULONG return values from this function are a proper superset of the DisplayInfo.NotAvailable field (defined in <graphics/displayinfo.h>).

The graphics library checks for the presence of the ECS chips at power up, but the monitor attached to the system cannot be detected and so must be specified by the user through a separate utility named “AddMonitor”.

Accessing the MonitorSpec

The OpenMonitor() function will locate and open the requested MonitorSpec. It is called with either the name of the monitor or a ModeID.

mspc = struct MonitorSpec *OpenMonitor(STRPTR name, ULONG modeID)

If the name argument is non-NULL, the MonitorSpec is chosen by name. If the name argument is NULL, the MonitorSpec is chosen by ModeID. If both the name and ModeID arguments are NULL, a pointer to the MonitorSpec for the default monitor is returned. OpenMonitor() returns either a pointer to a MonitorSpec structure, or NULL if the requested MonitorSpec could not be opened. The CloseMonitor() function relinquishes access to a MonitorSpec previously acquired with OpenMonitor().

To set up a View a ViewExtra structure must also be created and attached to it. The ViewExtra.Monitor field must be initialized to the address of a valid MonitorSpec structure before the View is displayed. Use OpenMonitor() to initialize the Monitor field.

Mode Properties

Here is an example of how to query the properties of a given mode from a DisplayInfoHandle.

#include <graphics/displayinfo.h>

check_properties( handle )

DisplayInfoHandle handle;

{

struct DisplayInfo queryinfo;

/* fill in the displayinfo buffer with basic Mode display data */

if(GetDisplayInfoData(handle, (UBYTE *)&queryinfo,sizeof(queryinfo),DTAG_DISP,NULL)))

{

/* check for Properties of this Mode */

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags)

{

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_LACE)

printf("mode is interlaced");

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_DUALPF)

printf("mode has dual playfields");

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_PF2PRI)

printf("mode has playfield two priority");

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_HAM)

printf("mode uses hold-and-modify");

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_ECS)

printf("mode requires the ECS chip set");

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_PAL)

printf("mode is naturally displayed on pal.monitor");

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_SPRITES)

printf("mode has sprites");

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_GENLOCK)

printf("mode is compatible with genlock displays");

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_WB)

printf("mode will support workbench displays");

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_DRAGGABLE)

printf("mode may be dragged to new positions");

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_PANELLED)

printf("mode is broken up for scan conversion");

if(queryinfo.PropertyFlags & DIPF_IS_BEAMSYNC)

printf("mode supports beam synchronization");

}

}

}

Nominal Values

Some of the display information is initialized in ROM for each mode such as recommended nominal (or default) dimensions. Even though this information is presumably static, it would still be a mistake to hardcode assumptions about these nominal values into your code.

Gathering information about the nominal dimensions of various modes is handled in a fashion similar to to the basic queries above. Here is an example of how to query the nominal dimensions of a given mode from a DisplayInfoHandle.

#include <graphics/displayinfo.h>

check_dimensions( handle )

DisplayInfoHandle handle;

{

struct DimensionInfo query;

/* fill the buffer with Mode dimension information */

if(GetDisplayInfoData(handle, (UBYTE *)&query,sizeof(query),DTAG_DIMS,NULL)))

{

/* display Nominal dimensions of this Mode */

printf("nominal width = %ld",

query.Nominal.MaxX - query.Nominal.MinX + 1);

printf("nominal height = %ld",

query.Nominal.MaxY - query.Nominal.MinY + 1);

}

}

Preference Items

Some display information is changed in response to user Preference specification. Until further notice, this will be reserved as a system activity and use private interface methods.

One Preferences setting that may affect the display data is the user’s preferred overscan limits to the monitor associated with this mode. Here is an example of how to query the overscan dimensions of a given mode from a DisplayInfoHandle.

#include <graphics/displayinfo.h>

check_overscan( handle )

DisplayInfoHandle handle;

{

struct DimensionInfo query;

/* fill the buffer with Mode dimension information */

if(GetDisplayInfoData(handle, (UBYTE *)&query,sizeof(query),DTAG_DIMS,NULL)))

{

/* display standard overscan dimensions of this Mode */

printf("overscan width = %ld",

query.StdOScan.MaxX - query.StdOScan.MinX + 1);

printf("overscan height = %ld",

query.StdOScan.MaxY - query.StdOScan.MinY + 1);

}

}

Run-Time Name Binding of Mode Information

It is useful to associate common names with the various display modes. The graphics library includes a provision for binding a name to a display mode so that it will be available via a query. This will be useful in the implementation of a standard screen-format requester. Note however that no names are bound initially since the bound names will take up RAM at all times. Instead defaults are used.

Bound names will override the defaults though, so that, until the screen-format requester is localized to a non-English language, the modes can be localized by binding foreign language names to them. Here is an example of how to query the run-time name binding of a given mode from a DisplayInfoHandle.

#include <graphics/displayinfo.h>

check_name_bound( handle )

DisplayInfoHandle handle;

{

struct NameInfo query;

/* fill the buffer with Mode dimension information */

if(GetDisplayInfoData(handle, (UBYTE *)&query,sizeof(query),DTAG_NAME,NULL)))

{

printf("%s", query.Name);

}

}

Custom ViewPort Example

The following program will create a display with the same attributes as the user’s Workbench screen. It does this by first inquiring as to those attributes, duplicating them, and then creating a similar display.

/**********************************************************************/

/* */

/* WBClone.c: To clone the Workbench using graphics calls */

/* */

/* Compile : SAS/C 5.10a LC -b1 -cfist -L -v -y */

/* */

/**********************************************************************/

#include <exec/types.h>

#include <exec/exec.h>

#include <clib/exec_protos.h>

#include <intuition/screens.h>

#include <intuition/intuition.h>

#include <intuition/intuitionbase.h>

#include <clib/intuition_protos.h>

#include <graphics/gfx.h>

#include <graphics/gfxbase.h>

#include <graphics/view.h>

#include <graphics/gfxnodes.h>

#include <graphics/videocontrol.h>

#include <clib/graphics_protos.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define INTUITIONNAME "intuition.library"

#ifdef LATTICE

int CXBRK(void) { return(0); } /* Disable Lattice CTRL/C handling */

int chkabort(void) { return(0); } /* really */

#endif

/*********************************************************************/

/* GLOBAL VARIABLES */

/*********************************************************************/

struct IntuitionBase *IntuitionBase = NULL ;

struct GfxBase *GfxBase = NULL ;

/**********************************************************************/

/* */

/* VOID Error (char *String) */

/* */

/* Print string and exit */

/* */

/**********************************************************************/

VOID Error (char *String)

{

VOID CloseAll (VOID) ;

printf (String) ;

CloseAll () ;

exit(0) ;

}

/**********************************************************************/

/* */

/* VOID Init () */

/* */

/* Opens all the required libraries allocates all memory, etc. */

/* */

/**********************************************************************/

VOID Init ( VOID )

{

/* Open the intuition library.... */

if ((IntuitionBase = (struct IntuitionBase *)OpenLibrary (INTUITIONNAME, 37L)) == NULL)

Error ("Could not open the Intuition.library") ;

/* Open the graphics library.... */

if ((GfxBase = (struct GfxBase *)OpenLibrary (GRAPHICSNAME, 36L)) == NULL)

Error ("Could not open the Graphics.library") ;

}

/**********************************************************************/

/* */

/* VOID CloseAll () */

/* */

/* Closes and tidies up everything that was used. */

/* */

/**********************************************************************/

VOID CloseAll ( VOID )

{

/* Close everything in the reverse order in which they were opened */

/* Close the Graphics Library */

if (GfxBase)

CloseLibrary ((struct Library *) GfxBase) ;

/* Close the Intuition Library */

if (IntuitionBase)

CloseLibrary ((struct Library *) IntuitionBase) ;

}

/**********************************************************************/

/* */

/* VOID DestroyView(struct View *view) */

/* */

/* Close and free everything to do with the View */

/* */

/**********************************************************************/

VOID DestroyView(struct View *view)

{

struct ViewExtra *ve;

if (view)

{

if (ve = (struct ViewExtra *)GfxLookUp(view))

{

if (ve->Monitor)

CloseMonitor(ve->Monitor);

GfxFree((struct ExtendedNode *)ve);

}

/* Free up the copper lists */

if (view->LOFCprList)

FreeCprList(view->LOFCprList);

if (view->SHFCprList)

FreeCprList(view->SHFCprList);

FreeVec(view);

}

}

/**********************************************************************/

/* */

/* struct View *DupView(struct View *v, ULONG ModeID) */

/* */

/* Duplicate the View. */

/* */

/**********************************************************************/

struct View *DupView(struct View *v, ULONG ModeID)

{

/* Allocate and init a View structure. Also, get a ViewExtra

* structure and attach the monitor type to the View.

*/

struct View *view = NULL;

struct ViewExtra *ve = NULL;

struct MonitorSpec *mspc = NULL;

if (view = AllocVec(sizeof(struct View), MEMF_PUBLIC | MEMF_CLEAR))

{

if (ve = GfxNew(VIEW_EXTRA_TYPE))

{

if (mspc = OpenMonitor(NULL, ModeID))

{

InitView(view);

view->DyOffset = v->DyOffset;

view->DxOffset = v->DxOffset;

view->Modes = v->Modes;

GfxAssociate(view, (struct ExtendedNode *)ve);

ve->Monitor = mspc;

}

else printf("Could not open monitor\n");

}

else printf("Could not get ViewExtra\n");

}

else printf("Could not create View\n");

if (view && ve && mspc)

return(view);

else

{

DestroyView(view);

return(NULL);

}

}

/**********************************************************************/

/* */

/* VOID DestroyViewPort(struct ViewPort *vp) */

/* */

/* Close and free everything to do with the ViewPort. */

/* */

/**********************************************************************/

VOID DestroyViewPort(struct ViewPort *vp)

{

if (vp)

{

/* Find the ViewPort's ColorMap. From that use VideoControl

* to get the ViewPortExtra, and free it.

* Then free the ColorMap, and finally the ViewPort itself.

*/

struct ColorMap *cm = vp->ColorMap;

struct TagItem ti[] =

{

{VTAG_VIEWPORTEXTRA_GET, NULL}, /* <-- This field will be filled in */

{VTAG_END_CM, NULL}

};

if (cm)

{

if (VideoControl(cm, ti) == NULL)

GfxFree((struct ExtendedNode *)ti[0].ti_Data);

else

printf("VideoControl error in DestroyViewPort()\n");

FreeColorMap(cm);

}

else

{

printf("Could not free the ColorMap\n");

}

FreeVPortCopLists(vp);

FreeVec(vp);

}

}