Copyright (c) Hyperion Entertainment and contributors.

Intuition Menus

Contents

- 1 Intuition Menus

- 2 About Menus

- 2.1 Types of Menu Choices

- 2.2 The Menu System

- 2.3 Menu Limitations

- 2.4 Setting Up Menus

- 2.5 Submitting and Removing Menu Strips

- 2.6 Simple Menu Example

- 2.7 Disabling Menu Operations

- 2.8 Changing Menu Strips

- 2.9 Sharing Menu Strips

- 2.10 Menu Selection Messages

- 2.11 Menu Numbers

- 2.12 Help Key Processing in Menus

- 2.13 Menu Layout

- 2.14 About Menu Item Boxes

- 2.15 Attribute Items and the Checkmark

- 2.16 Toggle Selection

- 2.17 Mutual Exclusion

- 2.18 Managing the State of Checkmarks

- 2.19 Command Key Sequences

- 2.20 Enabling and Disabling Menus and Menu Items

- 2.21 Intercepting Normal Menu Operations

- 2.21.1 A Warning on the MENUSTATE Flag

- 2.21.2 Menu Verify

- 2.21.3 Menu Verify and Double-Menu Requesters

- 2.21.4 Shortcuts and IDCMP_MENUVERIFY

- 2.21.5 IDCMP_MENUVERIFY and Deadlock

- 2.21.6 Reasons to Use Menu Verify

- 2.21.7 Reasons Not to Use Menu Verify

- 2.21.8 Will I Ever Need to Cancel a Menu Operation?

Intuition Menus

Menus are command and option lists associated with an application window that the user can bring into view at any time. These lists provide the user with a simple way to access features of the application without having to remember or enter complex character-based command strings.

The Intuition menu system handles all of the menu display without intervention from the application. The program simply submits an initialized list of data structures to Intuition and waits for menu events.

This section shows how to set up menus that allow the user to choose from your program's commands and options.

About Menus

Intuition's menu system provides applications with a convenient way to group together and display the commands and options available to the user. In most cases menus consist of a fixed list of text choices however this is not a requirement. Items in the menu list may be either graphic images or text, and the two types can be freely used together. The number of items in a menu can be changed if necessary.

Types of Menu Choices

Menu choices represent either actions or attributes. Actions are analogous to verbs. An action is executed and then forgotten. Actions include such things as saving and printing files, calculating values and displaying information on the program.

Attributes are analogous to adjectives. An attribute stays in effect until canceled. Attributes include such things as pen type, color, draw mode and numeric format.

For instance, in a word processor, menus could be used to control the following types of features:

- File loading and saving (action).

- Editing functions (action).

- Formatting preferences (attributes).

- Printing functions (action).

- Current font and style (attributes).

Menus can be set up such that some attribute items are mutually exclusive (selecting an attribute cancels the effects of one or more other attributes). For example, a drawing or graphics package may only allow one color to be active at a time; selecting a color cancels the previous active color.

The program can also allow a number of attributes to be in effect at the same time. A common example of this appears in most word processing programs, where the text style may be bold, italic or underlined. Selecting bold does not rule out italic or underlined, in fact, all three may be active at the same time.

The Menu System

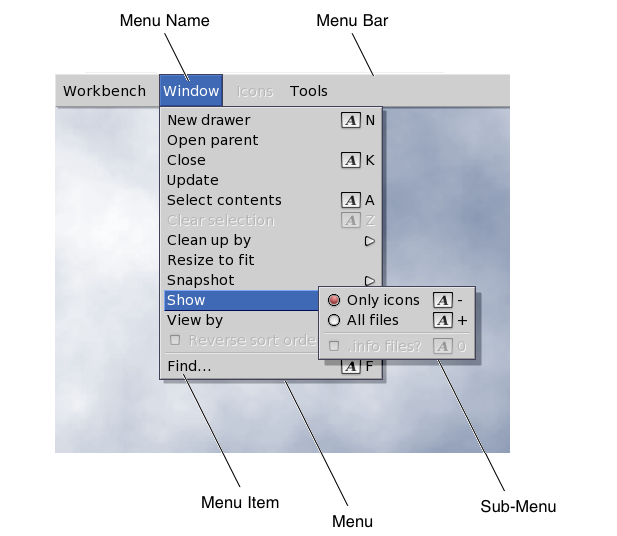

To activate the menu system, the user presses the menu button (the right mouse button). This displays the menu bar in the screen's title area. The menu bar displays a list of topics (called menus) that have menu items associated with them (see figure). The menu bar and menu items only remain visible while the menu button is held down.

When the mouse pointer is moved onto one of the menus in the menu bar, a list of menu items appears below the menu. The user can move the pointer within the list of menu items while holding down the menu button. A menu item will highlight when the pointer is over it and, if the item has a sub-item list, that list will be displayed.

The specific menu that is displayed belongs to the active window. Changing the active window will change the menu bar and the choices available to the user.

Unlike some other systems, the Amiga has no "standard menu" that appears in every menu bar. In fact, a window need not have any menus at all, thus holding down the mouse menu button does not guarantee the appearance of a menu bar. Although there is no "standard menu", the AmigaOS development team does have a well-defined set of standards for menu design. These standards are covered in the Amiga User Interface Style Guide.

Selecting Menu Items

To select a single menu item, the user releases the menu button when the pointer is over the desired item. Intuition can notify your program whenever the user makes a menu selection by sending an IDCMP message to your window's UserPort. Your application is then responsible for carrying out the action associated with the menu item selected. Action items lead to actions taken by the program while attribute items set values in the program for later reference.

Menu selection is restricted to the most subordinate item. Top level menus are never selected. A menu item can be selected as long as it has no sub-items, and a sub-item may always be selected. (Of course, disabled menu items and sub-items cannot be selected.)

Intuition menus allow the user to select multiple items by:

- Pressing and releasing the select button (left mouse button) without releasing the menu button. This selects the item and keeps the menus active so that other items may be selected.

- Holding down both mouse buttons and sliding the pointer over several items. This is called drag selecting. All items highlighted while dragging are selected.

Drag selection, single selection with the select button and releasing the mouse button over an item can all be combined in a single operation. Any technique used to select a menu item is also available to select a menu sub-item.

Menu Item Imagery

Menu items can be graphic images or text. There is no conceptual difference between menus that display text and menus that display images, in fact, the two techniques may be used together. The examples in this chapter use text based menus to avoid the extra code required to define images.

When the user positions the pointer over an item, the item can be highlighted through a variety of techniques. These techniques include a highlighted box around the selected item, complementing the entire item and replacing the item with an alternate image or alternate text.

Attribute items can have an image rendered next to them, usually a checkmark, to indicate whether they are in effect or not. The checkmark is positioned to the left of the item. If the checkmark is present, the attribute is on. If not, the attribute is off.

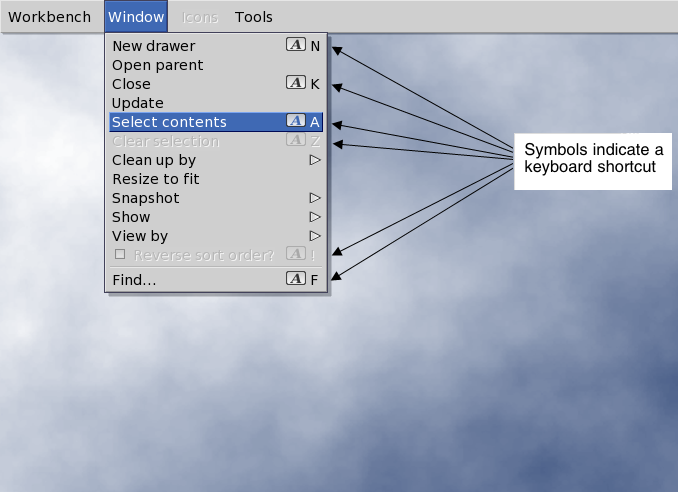

On the right side of menu items, command key alternatives may be displayed. Command key alternatives allow the user to make menu selections with the keyboard instead of the mouse. This is done by holding down the right Amiga key and then pressing the single character command key alternative listed next to the menu item. Command key alternatives appear as a reverse video, fancy "A", followed by the single character command key.

Menu items or whole menus may be enabled or disabled. Disabling an item prevents the user from selecting it. Disabled items are ghosted (overwritten with a pattern of dots making the image less distinct) in order to distinguish them from enabled items.

Menu help allows the application to be notified when the user presses the help key at the same time the menu system is activated. This allows applications to provide a help feature for every item in its menus. Menu help may be requested on any level of a menu.

Menu Limitations

Menus are not layered so they lock the screen while they are displayed. While the screen is locked, applications cannot render graphics into that screen; any rendering will be suspended until the menus are no longer displayed.

Menus can only display a limited number of choices. Each window may have up to 31 menus, each menu may have up to 63 items, and each item may have up to 31 sub-items.

Menus always appear at the top of the screen and cannot be repositioned or sized by the user. Moving the pointer to the menu bar may be inconvenient or time consuming for the user. (This is why it is generally a good idea to provide keyboard alternatives for menu items.) If some application has a function that the user will be performing repeatedly, it may be better to use a series of gadgets in the window (or a separate window) rather than a menu item.

Alternatives to Menus

You may want to use a requester or a window as an alternative to menus. A requester can function as a "super menu" using gadgets to provide the commands and options of a menu but with fewer restrictions on their placement, size and layout. See Intuition Requesters for more information.

A window, also, could be substituted for a menu where an application has special requirements. Unlike menus, windows allow layered operations so that commands and options can be presented without forcing all other window output in the active screen to halt.

Windows may be sized, positioned and depth arranged. This positioning flexibility allows the user to make other parts of the screen and other windows visible while they are entering data or selecting operations. The ability to access or view other data may be important in the user's choice of actions or attributes. See Intuition Windows for more details.

Setting Up Menus

The application does not have to worry about handling the menu display. The menus are simply submitted to Intuition and the application waits for Intuition to send messages about the selection of menu items. These messages, along with the data in the menu structures, give the application all the information required for the processing of the user actions.

Menus should be set up with the GadTools library. Since GadTools makes menu set up easier and handles much of the detail work of menu processing (including adjusting to the current font selection), it should be used whenever possible.

Under older versions of the OS, GadTools was not available. To set up menus that work with these older systems, you use the Menu and MenuItem structures. In general, for each menu in the menu bar, you declare one instance of the Menu structure. For each item or sub-item within a menu, you declare one instance of the MenuItem structure. Text-based menus like the kind used in this chapter require an additional IntuiText structure for each menu, menu item and sub-item. All these structures are defined in <intuition/intuition.h>.

The data structures used for menus are linked together to form a list known as a menu strip. For all the details of how the structures are linked and for listings of Menu and MenuItem, see the "Menu Structures" section later in this chapter.

Submitting and Removing Menu Strips

Once the application has set up the proper menu structures, linked them into a list and attached the list to a window, the menu system completely handles the menu display. The menu strip is submitted to Intuition and attached to the window by calling the function SetMenuStrip().

BOOL SetMenuStrip( struct Window *window, struct Menu *menu );

SetMenuStrip() always returns TRUE. This function can also be used to attach a single menu strip to multiple windows by calling SetMenuStrip() for each window (see below).

Any menu strip attached to a window must be removed before the window is closed. To remove the menu strip, call ClearMenuStrip().

VOID ClearMenuStrip( struct Window *window );

The menu example below demonstrates how to use these functions with a simple menu strip.

Simple Menu Example

Menu concepts are explained in great detail later in this chapter; for now though it may be helpful to look at an example. Here is a very simple example of how to use the Intuition menu system. The example shows how to set up a menu strip consisting of a single menu with five menu items. The third menu item in the menu has two sub-items.

The example works with all versions of the Amiga OS however it assumes that the Workbench screen is set up with the the Topaz 8 ROM font. If the font is different, the example will exit immediately since the layout of the menus depends on having a monospaced font with 8*8 pixel characters.

/* ** simplemenu.c: how to use the menu system with a window */ #include <exec/types.h> #include <exec/memory.h> #include <graphics/text.h> #include <intuition/intuition.h> #include <intuition/intuitionbase.h> #include <proto/exec.h> #include <proto/graphics.h> #include <proto/intuition.h> #include <string.h> /* These values are based on the ROM font Topaz8. Adjust these */ /* values to correctly handle the screen's current font. */ #define MENWIDTH (56+8) /* int32est menu item name * font width */ /* + 8 pixels for trim */ #define MENHEIGHT (10) /* Font height + 2 pixels */ struct GraphicsIFace *IGraphics = NULL; struct IntuitionIFace *IIntuition = NULL; /* To keep this example simple, we'll hard-code the font used for menu */ /* items. Algorithmic layout can be used to handle arbitrary fonts. */ /* GadTools provides font-sensitive menu layout. */ /* Note that we still must handle fonts for the menu headers. */ struct TextAttr Topaz80 = { "topaz.font", 8, 0, 0 }; struct IntuiText menuIText[] = { { 0, 1, JAM2, 0, 1, &Topaz80, "Open...", NULL }, { 0, 1, JAM2, 0, 1, &Topaz80, "Save", NULL }, { 0, 1, JAM2, 0, 1, &Topaz80, "Print \273", NULL }, { 0, 1, JAM2, 0, 1, &Topaz80, "Draft", NULL }, { 0, 1, JAM2, 0, 1, &Topaz80, "NLQ", NULL }, { 0, 1, JAM2, 0, 1, &Topaz80, "Quit", NULL } }; struct MenuItem submenu1[] = { { /* Draft */ &submenu1[1], MENWIDTH-2, -2 , MENWIDTH, MENHEIGHT, ITEMTEXT | MENUTOGGLE | ITEMENABLED | HIGHCOMP, 0, (APTR)&menuIText[3], NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL }, { /* NLQ */ NULL, MENWIDTH-2, MENHEIGHT-2, MENWIDTH, MENHEIGHT, ITEMTEXT | MENUTOGGLE | ITEMENABLED | HIGHCOMP, 0, (APTR)&menuIText[4], NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL } }; struct MenuItem menu1[] = { { /* Open... */ &menu1[1], 0, 0, MENWIDTH, MENHEIGHT, ITEMTEXT | MENUTOGGLE | ITEMENABLED | HIGHCOMP, 0, (APTR)&menuIText[0], NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL }, { /* Save */ &menu1[2], 0, MENHEIGHT , MENWIDTH, MENHEIGHT, ITEMTEXT | MENUTOGGLE | ITEMENABLED | HIGHCOMP, 0, (APTR)&menuIText[1], NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL }, { /* Print */ &menu1[3], 0, 2*MENHEIGHT , MENWIDTH, MENHEIGHT, ITEMTEXT | MENUTOGGLE | ITEMENABLED | HIGHCOMP, 0, (APTR)&menuIText[2], NULL, NULL, &submenu1[0] , NULL }, { /* Quit */ NULL, 0, 3*MENHEIGHT , MENWIDTH, MENHEIGHT, ITEMTEXT | MENUTOGGLE | ITEMENABLED | HIGHCOMP, 0, (APTR)&menuIText[5], NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL }, }; /* We only use a single menu, but the code is generalizable to */ /* more than one menu. */ #define NUM_MENUS 1 STRPTR menutitle[NUM_MENUS] = { "Project" }; struct Menu menustrip[NUM_MENUS] = { { NULL, /* Next Menu */ 0, 0, /* LeftEdge, TopEdge, */ 0, MENHEIGHT, /* Width, Height, */ MENUENABLED, /* Flags */ NULL, /* Title */ &menu1[0] /* First item */ } }; struct NewWindow mynewWindow = { 40,40, 300,100, 0,1, IDCMP_CLOSEWINDOW | IDCMP_MENUPICK, WFLG_DRAGBAR | WFLG_ACTIVATE | WFLG_CLOSEGADGET, NULL,NULL, "Menu Test Window", NULL,NULL,0,0,0,0,WBENCHSCREEN }; /* our function prototypes */ VOID handleWindow(struct Window *win, struct Menu *menuStrip); /* Main routine. */ /* */ int main(int argc, char **argv) { struct Window *win=NULL; uint16 left, m; /* Open the Graphics Library */ struct Library *GfxBase = IExec->OpenLibrary("graphics.library", 0); IGraphics = (struct GraphicsIFace*)IExec->GetInterface(GfxBase, "main", 1, NULL); struct Library *IntuitionBase = IExec->OpenLibrary("intuition.library", 0); IIntuition = (struct IntuitionIFace*)IExec->GetInterface(IntuitionBase, "main", 1, NULL); if (IGraphics && IIntuition) { if ( win = IIntuition->OpenWindow(&mynewWindow) ) { left = 2; for (m = 0; m < NUM_MENUS; m++) { menustrip[m].LeftEdge = left; menustrip[m].MenuName = menutitle[m]; menustrip[m].Width = TextLength(&win->WScreen->RastPort, menutitle[m], strlen(menutitle[m])) + 8; left += menustrip[m].Width; } if (IIntuition->SetMenuStrip(win, menustrip)) { handleWindow(win, menustrip); IIntuition->ClearMenuStrip(win); } IIntuition->CloseWindow(win); } } IExec->DropInterface((struct Interface*)IIntuition); IExec->CloseLibrary(IntuitionBase); IExec->DropInterface((struct Interface*)IGraphics); IExec->CloseLibrary(GfxBase); return 0; } /* ** Wait for the user to select the close gadget. */ VOID handleWindow(struct Window *win, struct Menu *menuStrip) { struct IntuiMessage *msg; BOOL done; uint32 class; uint16 menuNumber; uint16 menuNum; uint16 itemNum; uint16 subNum; struct MenuItem *item; done = FALSE; while (FALSE == done) { /* we only have one signal bit, so we do not have to check which ** bit broke the Wait(). */ IExec->Wait(1L << win->UserPort->mp_SigBit); while ( (FALSE == done) && (msg = (struct IntuiMessage *)IExec->GetMsg(win->UserPort))) { class = msg->Class; if(class == IDCMP_MENUPICK) menuNumber = msg->Code; switch (class) { case IDCMP_CLOSEWINDOW: done = TRUE; break; case IDCMP_MENUPICK: while ((menuNumber != MENUNULL) && (!done)) { item = IIntuition->ItemAddress(menuStrip, menuNumber); /* process this item ** if there were no sub-items attached to that item, ** SubNumber will equal NOSUB. */ menuNum = MENUNUM(menuNumber); itemNum = ITEMNUM(menuNumber); subNum = SUBNUM(menuNumber); /* Note that we are printing all values, even things ** like NOMENU, NOITEM and NOSUB. An application should ** check for these cases. */ IDOS->Printf("IDCMP_MENUPICK: menu %ld, item %ld, sub %ld\n", menuNum, itemNum, subNum); /* This one is the quit menu selection... ** stop if we get it, and don't process any more. */ if ((menuNum == 0) && (itemNum == 4)) done = TRUE; menuNumber = item->NextSelect; } break; } IExec->ReplyMsg((struct Message *)msg); } } }

Disabling Menu Operations

If an application does not use menus at all, it may set the WFLG_RMBTRAP flag, which allows the program to trap right mouse button events for its own use.

By setting the WFLG_RMBTRAP flag with the WA_Flags tag when the window is opened, the program indicates that it does not want any menu operations at all for the window. Whenever the user presses the right button while this window is active, the program will receive right button events as normal IDCMP_MOUSEBUTTONS events.

Changing Menu Strips

Direct changes to a menu strip attached to a window may be made only after the menu strip has been removed from the window. Use the ClearMenuStrip() function to remove the menu strip. It may be added back to the window after the changes are complete.

Major changes include such things as adding or removing menus, items and sub-items; changing text or image data; and changing the placement of the data. These changes require the system to completely re-layout the menus.

An additional function, ResetMenuStrip(), is available to let the application make small changes to the menus without the overhead of SetMenuStrip(). Only two things in the menu strip may be changed before a call to ResetMenuStrip(), they are: changing the CHECKED flag to turn checkmarks on or off, and changing the ITEMENABLED flag to enable/disable menus, items or sub-items.

BOOL ResetMenuStrip( struct Window *window, struct Menu *menu );

ResetMenuStrip() is called in place of SetMenuStrip(), and may only be called on menus that were previously initialized with a call to SetMenuStrip(). As with SetMenuStrip(), the menu strip must be removed from the window before calling ResetMenuStrip(). Note that the window used in the ResetMenuStrip() call does not have to be the same window to which the menu was previously attached. The window, however, must be on a screen of the same mode to prevent the need for recalculating the layout of the menu.

If the application wishes to attach a different menu strip to a window that already has an existing menu strip, the application must call ClearMenuStrip() before calling SetMenuStrip() with the new menu strip.

The flow of events for menu operations should be:

OpenWindowTagList()

.

SetMenuStrip()

.

Zero or more iterations of ClearMenuStrip() and SetMenuStrip() or ResetMenuStrip().

ClearMenuStrip()

.

CloseWindow()

.

Sharing Menu Strips

A single menu strip may be attached to multiple windows in an application by calling SetMenuStrip() for each window. All of the windows must be on the same screen for this to work. Since menus are always associated with the active window on a given screen, and since only one window may be active on a screen at a time, only one window may display the shared menu strip at any given time.

When multiple windows share a single menu strip, they will all "see" the same state of the menus, that is, changes made to the menu strip from one window will still exist when a new window is activated. If the application wishes to share menu strips but to have a different flag and enabled status for each window, the program may watch IDCMP_ACTIVEWINDOW for the windows and modify the menu strip to match the active window's requirements at that point. In addition, the application must also set IDCMP_MENUVERIFY to insure that the user can't access the menus of a newly activated window before the application can process the IDCMP_ACTIVEWINDOW message.

ResetMenuStrip() may also be used to set the menus for the multiple windows as long as SetMenuStrip() is used first to attach the menu strip to any one window and no major changes are made to the menu strip before the calls to ResetMenuStrip() on subsequent windows.

Menu Selection Messages

An input event is generated every time the user activates the menu system, either by pressing the mouse menu button or its keyboard equivalent (right Amiga Alt), or entering an appropriate command key sequence. The program receives a message of type IDCMP_MENUPICK detailing which menu items or sub-items were selected. Even if the user activates the menu system without selecting a menu item or sub-item, an event is generated.

Multi-Selection of Menu Items

Each activation of the menu system generates only a single event. The user may select none, one or many items using any of the selection techniques described above; still, only one event is sent.

The program finds out whether or not multiple items have been chosen by examining the field called NextSelect in the MenuItem structure. The selected items are chained together through this field. This list is only valid until the user next activates the menu system, as the items are chained together through the actual MenuItem structures used in the menu system. If the user reselects an item, the NextSelect field of that item will be overwritten.

In processing the menu events, the application should first take the appropriate action for the item selected by the user, then check the NextSelect field. If the number there is equal to the constant MENUNULL, there is no next selection. However, if it is not equal to MENUNULL, the user has selected another option after this one. The program should process the next item as well, by checking its NextSelect field, until it finds a NextSelect equal to MENUNULL.

The following code fragment shows the correct way to process a menu event:

struct IntuiMessage *msg; struct Menu *menuStrip; uint16 menuNumber = msg->Code; while (menuNumber != MENUNULL) { struct MenuItem *item = IIntuition->ItemAddress(menuStrip, menuNumber); /* process this item */ menuNumber = item->NextSelect; }

Intuition specifies which item or sub-item was selected in the IDCMP_MENUPICK event by using a shorthand code known as a menu number. Programs can locate the MenuItem structure that corresponds to a given menu number by using the ItemAddress() function. This function translates a menu number into a pointer to the MenuItem structure represented by the menu number.

struct MenuItem *ItemAddress( struct Menu *menuStrip, ULONG menuNumber );

This allows the application to gain access to the MenuItem structure and to correctly process multi-select events. Again, when the user performs multiple selection, the program will receive only one message of class IDCMP_MENUPICK. For the program to behave correctly, it must pay attention to the NextSelect field of the MenuItem, which will lead to the other menu selections.

There may be some cases in an application's logical flow where the selection of a menu item voids any further menu processing. For instance, after processing a "quit" menu selection, the application will, in general, ignore all further menu selections.

Menu Numbers

The menu numbers Intuition provides in the IDCMP_MENUPICK messages, describe the ordinal position of the menu in the linked list of menus, the ordinal position of the menu item beneath that menu, and (if applicable) the ordinal position of the sub-item beneath that menu item. Ordinal means the successive number of the linked items, in this case, starting from 0.

To determine which menus and menu items (sub-items are special cases of menu items) were selected, use the following macros:

| MENUNUM(num) | Extracts the ordinal menu number from num. |

| ITEMNUM(num) | Extracts the ordinal item number from num. |

| SUBNUM(num) | Extracts the ordinal sub-item number from num. |

MENUNULL is the constant describing "no menu selection made." Likewise, NOMENU, NOITEM, and NOSUB describe the conditions "no menu chosen," "no item chosen" and "no sub-item chosen."

For example:

if (menuNumber == MENUNULL) /* no menu selection was made */ ; else { /* if there were no sub-items attached to that item, ** SubNumber will equal NOSUB. */ menuNum = MENUNUM(menuNumber); itemNum = ITEMNUM(menuNumber); subNum = SUBNUM(menuNumber); }

The menu number received by the program is always set to either MENUNULL or a valid menu selection. If the menu number represents a valid selection, it will always have at least a menu number and a menu item number. Users can never select the menu text itself, but they always select at least an item within a menu. Therefore, the program always gets at least the menu selected and the menu item selected. If the menu item selected has a sub-item, a sub-item number will also be received.

Just as it is not possible to select an entry in the menu bar, it is not possible to select a menu item that has attached sub-items. The user must select one of the options in the sub-item list before the program hears about the action as a valid menu selection.

| Help Is Available |

|---|

| The restrictions on what can be selected do not apply to IDCMP_MENUHELP messages. Using menu help, a user can select any component of a menu, including the menu header itself. |

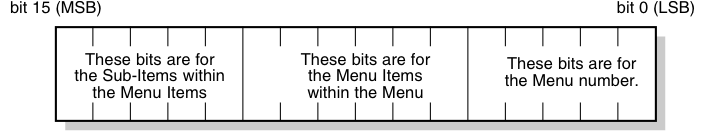

How Menu Numbers Really Work

The following is a description of how menu numbers really work. It should clarify why there are some restrictions on the number of menu components Intuition allows. Programs should not rely on the information given here to access menu number information directly though. Always use the Intuition menu macros to handle menu numbers.

For convenience you should use the menus supplied. For example, to extract the item number from the menu number, call the macro ITEMNUM(menu_number); to construct a menu number, call the macro FULLMENUNUM(menu, item, sub). See the section at the end of this chapter for a more complete description of the menu number macros.

Menu numbers are 16-bit numbers with 5 bits used for the menu number, 6 bits used for the menu item number, and 5 bits used for the sub-item number. The three numbers only have meaning when used together to determine the position of the item or sub-item selected.

The value "all bits on" means that no selection of this particular component was made. MENUNULL actually equals "no selection of any of the components was made" so MENUNULL always equals "all bits of all components on."

For example, suppose that the program gets back the menu number (in hexadecimal) 0x0CA0. In binary that equals:

Again, the application should not examine these numbers directly. Use the macros described above to ensure proper menu handling.

Help Key Processing in Menus

If the window is opened with the WA_MenuHelp tag, then user selection of the help key while menus are displayed will be detected.

When the user presses the Help key while using the menu system, the menu selection is terminated and an IDCMP_MENUHELP event is sent. The IDCMP_MENUHELP event is sent in place of the IDCMP_MENUPICK event, not in addition to it. IDCMP_MENUHELP never come as multi-select items, and the event terminates the menu processing session.

The routine that handles the IDCMP_MENUHELP events must be very careful; it can receive menu information that is impossible under IDCMP_MENUPICK. IDCMP_MENUHELP events may be sent for any menu, item or sub-item in the menu strip, regardless of its state or position in the list. The program may receive events for items that are disabled or ghosted. IDCMP_MENUHELP events may send the menu header number alone, or the menu and item numbers, or all three components regardless of the items linked to the selected menu or item. This is done because it is reasonable for a user to request help in a disabled item or a menu header. If the user requests menu help on a disabled menu item or sub-item, try to explain to the user why that item is disabled and what steps are necessary to enable it. For instance, pressing help while a menu header is highlighted will trigger an IDCMP_MENUHELP event with a code that has a valid number for the menu, then NOITEM and NOSUB (IDCMP_MENUPICK would receive MENUNULL in this case.)

The application should not take the action indicated by the IDCMP_MENUHELP event, it should provide the user with a description of the use or status of that menu. The application should never step through the NextSelect chain when it receives a IDCMP_MENUHELP event.

Menu Layout

The Amiga allows great flexibility in the specification of fonts for the display. Default fonts are chosen by the user to suit their particular requirements and display resolution. The application should, where possible, use one of the preferred fonts.

If the application did not open its own screen and completely specify the font for that screen, it must perform dynamic menu layout. This is because the Menu structure does not specify font. The menu header always uses the screen font and the program should update the size and position of these items at runtime to reflect the font.

The font for menu items may be specified in the MenuItem structure, allowing the programmer to hard code values for the font, size and position of these items. This is not recommended. A specific font, while ideal on one system, may be less than ideal on another display type. Use the preferred font wherever possible.

If the application does its own menu layout, it must use great care to handle the font in the menu strip and the font in each item or sub-item. The code should also keep items from running off the edges of the screen.

See the description of ItemFill in the section "MenuItem Structure" below for information on the positioning of multiple IntuiText or Image structures within the menu item.

Applications should use the GadTools library menu layout routines whenever possible, rather than performing their own layout. See GadTools Library for more details.

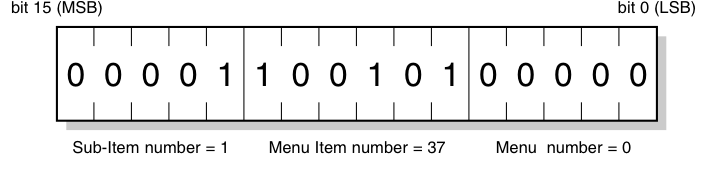

About Menu Item Boxes

The item box is the rectangle containing the menu items or sub-items.

The size and location of the item or sub-item boxes is not directly described by the application. Instead, the size is indirectly described by the placement of items and sub-items. When presented with a menu strip, Intuition first calculates the minimum size box required to hold the items. It then adjusts the box to ensure the menu display conforms to certain design philosophy constraints for items and sub-items.

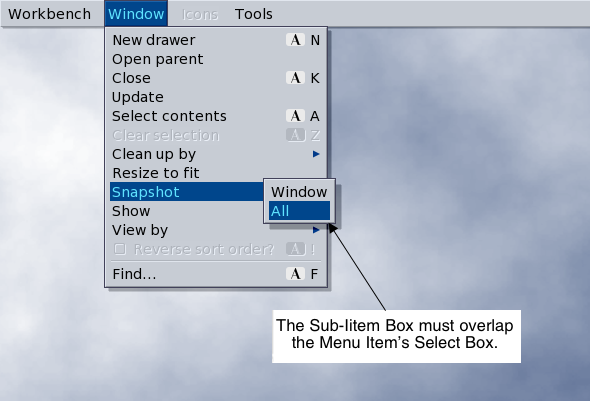

The item box must start no further right than the leftmost position of the menu header's select box. It must end no further left than the rightmost position of the menu header's select box. The top edge of each item box must overlap the screen's title bar by one line. Each sub-item box must overlap its item's select box somewhere.

Attribute Items and the Checkmark

Attribute items are items that have two states: selected and unselected. In the menu system, these items are often represented as items with checkmarks. If the checkmark is visible, then the item (or attribute) is selected. Otherwise, the attribute is not selected.

Checkmarked items (attributes) may be toggle selected or mutually exclusive. Selecting a toggle selected item toggles its state; if it was selected, it will become unselected; and if it was unselected, it will become selected. Selecting a mutually exclusive item puts it in the selected state, while possibly clearing one or more other items, where it remains until it is cleared by the selection of some other item.

A menu item is specified as a checkmark item by setting the CHECKIT flag in the Flags variable of the item's MenuItem structure.

The program can initialize the state of the checkmark (checked or not) by presetting the item's CHECKED flag. If this flag is set when the menu strip is submitted to Intuition, then the item is considered selected and the checkmark will be drawn.

The program can use the default Intuition checkmark or provide a custom checkmark for the menus. To use a custom checkmark, the application must provide a pointer to the image with the WA_Checkmark tag when the window is opened. See Intuition Windows for details about supplying a custom checkmark.

The application must provide sufficient blank space at the left edge of the select box for the checkmark imagery. Constants are provided to standardize the space reserved in the menu for the checkmark. LOWCHECKWIDTH gives the amount of space required for checkmarks on low resolution screens and CHECKWIDTH gives space for all other screens.

These constants specify the space required by the default checkmarks (with a bit of space for aesthetic purposes). If the image would normally be placed such that the LeftEdge of the image without the checkmark is 5, the image should start at 5 + CHECKWIDTH if CHECKIT is set. Also, the select box must be made CHECKWIDTH wider than it would be without the checkmark. It is generally accepted on the Amiga that only checkmarked items should be indented by the size of the checkmark, other items are left justified within their column.

Toggle Selection

Some of the checkmarked menu items may be of the toggle select type. Each time the user accesses such an item, it changes state, selected or unselected. To make an attribute item toggle select, set both the CHECKIT and the MENUTOGGLE flags for that menu item. Of course, the CHECKED flag may be preset to the desired initial state.

Mutual Exclusion

Mutual exclusion allows the selection of an item to cause other items to become unselected.

For example, for a list of menu items describing the available sizes for a font, the selection of any size could unselect all other sizes. Use the MutualExclude variable in the MenuItem structure to specify other menu items to be excluded when the user selects an item. Exclusion also depends upon the CHECKED and CHECKIT flags of the MenuItem, as explained below.

If CHECKED is not set, then this item is available to be selected. If the user selects this item, the CHECKED flag is set and the checkmark will be drawn to the left of the item.

If the item selected has bits set in the MutualExclude field, the CHECKED flag is examined in the excluded items. If any item is currently CHECKED, its checkmark is erased, and its CHECKED flag is cleared.

Mutual exclusion pertains only to items that have the CHECKIT flag set. Attempting to exclude items that do not have the CHECKIT flag set has no effect.

| Keep track of deselected items |

|---|

| It is up to the program to track internally which excluded items have been deselected. See the section "Enabling and Disabling Menus and Menu Items" below for more information. |

In the MutualExclude field, bit 0 refers to the first item in the item list, bit 1 to the second, bit 2 to the third, and so on.

In the text style example described above, selecting plain excludes any other style. The MutualExclude fields of the four items would look like this:

| Plain | 0xFFFE |

| Bold | 0x0001 |

| Italic | 0x0001 |

| Underline | 0x0001 |

"Plain" is the first item on the list. It excludes all items except the first one. All of the other items exclude only the first item, so that bold, underlined text may be selected, while bold, plain text may not.

Managing the State of Checkmarks

To correctly handle checkmarked menu items, from time to time the application will need to read the CHECKED bit of its CHECKIT MenuItems. It is not adequate to infer which items are checked by tracking what their state must have become. There are several reasons for this (although it's not important to understand the details; just the implication):

- Using multi-selection of menus, the user can toggle the state of a MENUTOGGLE item several times, yet the application will receive only a single IDCMP_MENUPICK event, and that item will only appear once in the NextSelect chain.

- When the user selects a mutually exclusive menu item, the IDCMP_MENUPICK event refers to that item, but Intuition doesn't notify your application of other items that may have been deselected through mutual exclusion.

- For complex multi-selection operations, the NextSelect chain will not be in select-order (a side-effect of the fact that the same MenuItem cannot appear twice in the same NextSelect chain combined with the fix to the orphaning problems mentioned above). With certain mutual exclusion arrangements, it is impossible to predict the state of the checkmarks.

- If the user begins multi-selection in the menus and hits several checkmarked items, but then presses the help key, the application will receive an IDCMP_MENUHELP message. No IDCMP_MENUPICK message will have been sent. Thus, some checkmark changes could have gone unnoticed by the application.

It is legal to examine the CHECKED state of a MenuItem while that MenuItem is still attached to a window. It is unnecessary to first call ClearMenuStrip().

Command Key Sequences

A command key sequence is an event generated when the user holds down one of the Amiga keys (the ones with the fancy A) and presses one of the normal alphanumeric keys at the same time. There are two different command or Amiga keys, commonly known as the left Amiga key and the right Amiga key.

Menu command key sequences are combinations of the right Amiga key with any alphanumeric character, and may be used by any program. These sequences must be accessed through the menu system. Command key sequences using the left Amiga key cannot be associated with menu items.

Menu command key sequences, like the menus themselves, are only available for a window while that window is active. Each window may control these keys by setting keyboard shortcuts in the menu item structures which make up the window's menu strip.

If the user presses a command key sequence that is associated with one of the menu items, Intuition will send the program an event that is identical to the event generated by selecting that menu item with the mouse. Many users would rather keep their hands on the keyboard than use the mouse to make a menu selection when accessing often repeated selections. Menu command key sequences allow the program to provide shortcuts to the user who prefers keyboard control.

A command key sequence is associated with a menu item by setting the COMMSEQ flag in the Flags variable of the MenuItem structure and by placing the ASCII character (upper or lower case) that is to be associated with the sequence into the Command variable of the MenuItem structure.

Command keys are not case sensitive and they do not repeat. Command keys are processed through the keymap so that they will continue to work even if the key value is remapped to another position. International key values are supported as long as they are accessible without using the Alt key (right-Amiga-Alt maps to the right mouse button on the mouse).

When items have alternate key sequences, the menu boxes show a special Amiga key glyph rendered roughly one character span plus a few pixels from the right edge of the menu select box. The command key used with the Amiga key is displayed immediately to the right of the Amiga key image, at the rightmost edge of the menu select box (see figure).

Space must be provided at the right edge of the select box for the Amiga key imagery and for the actual command character. Leave COMMWIDTH pixels on high resolution screens, and LOWCOMMWIDTH pixels on low resolution screens. The character's width may be calculated with the graphics library TextLength() call. In general, each column of items should leave enough room for the widest command character plus the width of the Amiga key imagery.

Enabling and Disabling Menus and Menu Items

Disabling menu items makes them unavailable for selection by the user.

Disabled menus and menu items are displayed in a ghosted fashion; that is, their imagery is overlaid with a faint pattern of dots, making it less distinct.

Enabling or disabling a menu or menu item is always a safe procedure, whether or not the user is currently using the menus. Of course, by the time you have disabled the item, the user may have already selected it. Thus, the program may receive a IDCMP_MENUPICK message for that item, even though it considers the item disabled. The program should be prepared to handle this case and ignore items that it knows are already disabled. This implies that the program must track internally which items are enabled and which are disabled.

The OffMenu() and OnMenu() functions may be used to enable or disable items while a menu strip is attached to the window.

VOID OffMenu( struct Window *window, ULONG menuNumber ); VOID OnMenu( struct Window *window, ULONG menuNumber );

These routines check if the user is currently using the menus and whether the menus need to be redrawn to reflect the new states. If the menus are currently in use, these routines wait for the user to finish before proceeding.

If the item component referenced by menuNumber equals NOITEM, the entire menu will be disabled or enabled. If the item component equates to an actual component number, then that item will be disabled or enabled. Use the macros defined below for the construction of menu numbers from their component parts.

The program can enable or disable whole menus, just the menu items, or just single sub-items.

- To enable or disable a whole menu, set the item component of the menu number to NOITEM. This will enable or disable all items and any sub-items for that menu.

- To enable or disable a single item and all sub-items attached to that item, set the item component of the menu number to the item's ordinal number. If the item has a sub-item list, set the sub-item component of the menu number to NOSUB. If the item has no sub-item list, the sub-item component of the menu number is ignored.

- To enable or disable a single sub-item, set the item and sub-item components appropriately.

It is also legal to remove the menu strip from each window that it is attached to (with ClearMenuStrip() ) change the ITEMENABLED or MENUENABLED flag of one or more Menu or MenuItem structures and add the menu back using ResetMenuStrip() or SetMenuStrip().

Intercepting Normal Menu Operations

IDCMP_MENUVERIFY gives the program the opportunity to react before menu operations take place and, optionally, to cancel menu operations. Menus may be completely disabled by removing the menu strip with a call to ClearMenuStrip().

A Warning on the MENUSTATE Flag

The MENUSTATE flag is set by Intuition in Window.Flags when the menus of that window are in use. Beware: in typical event driven programming, such a state variable is not on the same timetable as the application's input message handling, and should not be used to draw profound conclusions in any program. Use IDCMP_MENUVERIFY to synchronize with the menu handling.

Menu Verify

Menu verify is one of the Intuition verification capabilities that allow an application to ensure that it is prepared for some action taken by Intuition before that action takes place. Through menu verify, Intuition allows all windows in a screen to verify that they are prepared for menu operations before the operations begin. In general, use menu verify if the program is doing something special to the display of a custom screen, and needs to be sure the operation has completed before menus are rendered.

Menu verification works using the IDCMP mechanism. For an Intuition screen, when the user triggers Intuition into drawing the menu, Intuition sends an IDCMP_MENUVERIFY message to every window on that screen that asked to hear about menu verify events. Intuition will not display the menus until it gets back all the IDCMP_MENUVERIFY messages.

Any window can access the menu verify feature by setting the IDCMP_MENUVERIFY flag with the WA_IDCMP tag when opening the window. When menus are activated in a screen which contains at least one window with IDCMP_MENUVERIFY set, menu operations will not proceed until all windows with the menu verify flag set reply to the notification or until the last message times out. The specific menu verify protocol is described below.

It is vital that the application know when menu operations terminate, for only then does it have control of the screen again.

It is not recommended that your programs try and interpret the cause of a menu cancellation. The reasoning for the cancellation is not really relevant. Trying to interpret the cause of a menu cancellation is a bad idea. The only important fact is that the "menu processing" state has terminated and the application can resume normal operations.

Any of the following message combinations signify the cancellation of the "menu processing" state:

- IDCMP_MOUSEBUTTONS (IntuiMessage.Code is equal to MENUUP) only

- IDCMP_MENUPICK (IntuiMessage.Code is equal to MENUNULL) only

- IDCMP_MOUSEBUTTONS (IntuiMessage.Code is equal to MENUUP) then IDCMP_MENUPICK (IntuiMessage.Code is equal to MENUNULL)

- IDCMP_MENUPICK (IntuiMessage.Code is equal to MENUNULL) then IDCMP_MOUSEBUTTONS (IntuiMessage.Code is equal to MENUUP)

Since the active window can cancel menu operations, the application may need to determine if its window is the active window. The application can do this by examining the IntuiMessage.Code field of the menu verify message. If that field is equal to MENUWAITING the window is not active. However, if that field is equal to MENUHOT the window is active and can cancel the menu operation by changing the Code field of the menu verify message to MENUCANCEL. If the application cancels the menu operation, Intuition will send the active window an IDCMP_MOUSEBUTTONS event about the right mouse button.

The following are possible cases signifying that the "menu processing" state is over because the user successfully pulled down and released the menu (there was no cancellation):

- IDCMP_MENUPICK (IntuiMessage.Code is equal to the menu code)

- (spurious) IDCMP_MOUSEBUTTONS (IntuiMessage.Code is equal to MENUUP) then IDCMP_MENUPICK (IntuiMessage.Code is equal to the menu code)

Note that the menu code could be MENUNULL if no item was selected. IDCMP_MENUHELP events have the same meaning as the IDCMP_MENUPICK messages when it comes to terminating the "menu processing" state.

Active Window

The active window is given special menu verify treatment. It receives the menu verify message before any other window and has the option of canceling menu operations altogether. This could be used, for instance, to examine where the user has positioned the mouse when the right button was pressed. For example, the application may choose to allow normal menu operations to proceed only when the pointer is in the menu bar area. When the pointer is below the menu bar, then the application can choose to interpret the menu verify message as a right button event for some non-menu purpose.

If it wishes menu operations to proceed, the active window should reply to the IDCMP_MENUVERIFY message without changing any values. To cancel the menu operation, change the code field of the message to MENUCANCEL before replying to the message as described above.

The system takes no action on screen until the active window either replies to the menu verify event or the event times out. If the active window replies to the event in time and does not cancel the menu operation, Intuition will then move the screen title bar layer to the front, display the menu strip and notify all inactive menu verify windows of the operation. Layers will not be locked and the actual menus will not be swapped in until all these inactive windows reply to the message or time out.

Inactive Windows

When menu operations terminate, inactive windows will always receive IDCMP_MOUSEBUTTONS message with code equal to MENUUP.

Inactive windows may not cancel a menu operation.

If an inactive window receives an IDCMP_MENUVERIFY message, it will always receive an IDCMP_MOUSEBUTTONS message with code equal to MENUUP when the menu operations are completed.

Menu Verify and Double-Menu Requesters

The processing described above becomes more complicated when double-menu requester processing is introduced. If an application chooses to use a double-menu requester in a window with IDCMP_MENUVERIFY set, it should be aware that odd message combinations are possible. For instance, it is possible to receive only an IDCMP_MENUVERIFY event with no following IDCMP_MOUSEBUTTONS event or IDCMP_MENUPICK event. Applications should avoid using double menu requesters if possible.

The double menu requester is considered to be inconsistant with the Amiga's user interface, so using them in any capacity is strongly discouraged. Using them in conjunction with menu verify is even more strongly discouraged because they significantly complicate processing menu verify events. For this reason, never use double menu requester and menu verify together.

Shortcuts and IDCMP_MENUVERIFY

The idea behind IDCMP_MENUVERIFY is to synchronize the program with Intuition's menu handling sessions. The motive was to allow a program to arbitrate access to a custom screen's bitmap, so that Intuition would not render menus before the application was prepared for them.

Some programs use IDCMP_MENUVERIFY to permit them to intercept the right mouse button for their own purposes. Other programs use it to delay menu operations while they recover from unusual events such as illegible colors of the screen or double buffering and related ViewPort operations.

Menu shortcut keystrokes, for compatibility, also respect IDCMP_MENUVERIFY. They are always paired with an IDCMP_MENUPICK message so that the program knows the menu operation is over. This is true even if the menu event is cancelled.

IDCMP_MENUVERIFY and Deadlock

The program may call ModifyIDCMP() to turn IDCMP_MENUVERIFY and the other VERIFY IDCMP options off. It is important that this be done each and every time that the application is directly or indirectly waiting for Intuition, since Intuition may be waiting for the application, but not watching the window message port for IDCMP_MENUVERIFY events. The program cannot wait for a gadget or mouse event without checking also for any IDCMP_MENUVERIFY event messages that may require program response.

The most common problem area is System Requesters (AutoRequest() and EasyRequest()). Before AutoRequest() and EasyRequest() return control to the application, Intuition must be free to run and accept a response from the user. If the user presses the menu button, Intuition will wait for the program to reply to the IDCMP_MENUVERIFY event and a deadlock results.

Therefore, it is extremely important to use ModifyIDCMP() to turn off all verify messages before calling AutoRequest(), EasyRequest() or, directly or indirectly, AmigaDOS, since many error conditions in the DOS require user input in the form of an EasyRequest(). Indirect DOS calls include OpenLibrary(), OpenDevice(), and OpenDiskFont().

All windows that have the IDCMP_MENUVERIFY bit set must respond to Intuition within a set time period, or the menu operation will time out and the menu action will be canceled.

| IDCMP_MENUVERIFY Timeout |

|---|

| Intuition has a time out on menu verify operations. If the active window's application takes too long to respond to the IDCMP_MENUVERIFY message, Intuition will cancel the menu operation. This feature helps avoid some deadlocks that can occur while Intuition is waiting on the active window. This feature applies only to the active window; Intuition will wait indefinitely for the IDCMP_MENUVERIFY message from an inactive window. |

Reasons to Use Menu Verify

The primary purpose of the menu verify feature is to arbitrate access to screen resources. There are really only two screen resources that an application might need to use directly, the palette and the bitmap.

Some applications need as many pens as possible, so they change the color values of the pens that Intuition uses to render the menus. This can present a problem if the application happens to alter the menu pen colors so that the menu's foreground color is difficult (if not impossible) to see against the background color. The menu items will be unreadable to the user.

To prevent this problem, the application has to restore the original pen colors when the user pulls down the menu. The application can do this using menu verify. When the user hits the menu button, Intuition sends the application a menu verify message. When the application receives this message, it restores the menu colors and then returns the IDCMP_MENUVERIFY message so Intuition can properly render the menus. When the menu operation is over, Intuition will send a "conclusion" IDCMP message. The "conclusion" message is covered below.

Another reason to use menu verify is to arbitrate rendering access to an Intuition Screen's bitmap. While Intuition is displaying the menus, the application must not render directly to the screen's bitmap because the application could draw over the menus. The application must wait until the menu operation is over to resume rendering.

This raises some important questions. Why render into a screen's bitmap (Screen-> RastPort.BitMap)? Shouldn't I render into a window instead?

The quick answer is: "render into a window's rastport instead of rendering directly into a screen's bitmap." Rendering to a window's rastport offers several advantages over rendering directly to the screen's bitmap. The window offers the application efficient clipping, making the application simpler because it doesn't need to worry about rendering into rectangular bounds. The window also supports a layered display, so the application can ignore the consequences of arbitrating access to the screen's bitmap.

There are some cases where, arguably, it might be advantageous for an application to render directly into a screen's bitmap. Rendering into a screen's bitmap versus rendering to a window's rastport offers a slight improvement in performance. Part of this improvement is due to the lack of clipping on a screen's bitmap, which the window provides, so the performance improvement is questionable if you still need to perform clipping.

One case where an application has to render into a screen's bitmap is when graphics functions that operate below the layers level. For example blitter objects (BOBs) operate below the layers level. If the application is operating below the layers level, it can't render to a windowed display.

Reasons Not to Use Menu Verify

One feature of Intuition menus is that the user can toggle a menu item between a selected "checked" state and an unselected "unchecked" state. Intuition keeps track of the state, so the application only has to read the state from the MenuItem structure. In some cases, the state of the menu item can be affected by something besides the user performing menu operations, so the application has to explicitly change the state of the menu item.

Some applications use the menu verify feature as a mechanism for updating the state of the menu items. When such an application receives the IDCMP_MENUVERIFY message, it updates the checked flag of the menu items and then returns the menu verify message. Some applications also use this method to manage the enabled and disabled state of a menu item.

Although this method works, it should not be necessary to interrupt the menu event. Almost all applications should be able to keep their menu states current using ResetMenuStrip(). It is also possible to use SetMenuStrip(), but since ResetMenuStrip() is considerably faster than SetMenuStrip(), ResetMenuStrip() is better. See the Autodoc for ResetMenuStrip() for more details.

Some people may think one potential use for menu verify is to assign an alternative meaning to the right mouse button. For example, when the pointer is not within the title bar of a screen, some paint packages use the right mouse button to paint using the background color. Using menu verify, it is possible for a application to intercept the menu verify event, checking to see if the pointer is within the title bar. If it isn't, the application cancels the menu event. After cancelling the menu event, Intuition will send a right button down event, which the application can interpret.

This mechanism may work, but it is not very efficient. There is a better way to do this using WFLG_RMBTRAP. This flag is from the Flags field in the Window structure. When set, this flag disables menu operations for the window. When the user hits the menu button, Intuition sends the window IDCMP_MOUSEBUTTONS events instead of menu events.

To use WFLG_RMBTRAP as an alternative to menu verify, the application tracks mouse movement using IDCMP_MOUSEMOVE. While the pointer is outside of the screen's title bar, the application makes sure the WFLG_RMBTRAP flag is set. If the user hits the right mouse button while WFLG_RMBTRAP is set, Intuition sends the application a mouse button event. While the pointer is inside the screen's title bar, the application makes sure the WFLG_RMBTRAP flag is clear. If the user hits the right mouse button while WFLG_RMBTRAP is clear, Intuition generates a normal menu event for the window.

WFLG_RMBTRAP is an exception to most fields in Intuition structures because it is legal for an application to directly modify this flag. Note that this change must take place as an atomic operation so that Exec cannot perform a task switch in the middle of the change. If you are unsure your compiler will do this, use a Forbid()/Permit() pair to prevent a task switch.

There are cases where an application is too busy to handle any menu event so it needs to prevent menu operations for a while. This is another case where menu verify is inappropriate. A better way to block menus is to remove the menu with the Intuition function ClearMenuStrip() and restore it later with ResetMenuStrip(). Another potentially useful way to block menu operations is using a requester.

Will I Ever Need to Cancel a Menu Operation?

When the active window receives an IDCMP_MENUVERIFY message, it has the option of cancelling the menu operation. Although this feature may have some possible uses, for the moment there is no recommended use for it.